Young Artists Develop Portfolios — and Their Futures

A West Virginia graphic design teacher prepares “challenged” students for college and creative careers.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Doug Martin knows all about the arid landscape of unrecognized intelligence; he's been there.

"When I was in school," he recalls, "the only gifts that were embraced as intelligent were reading, writing, and arithmetic. I couldn't imagine going to college at that time, because I didn't feel smart enough in the traditional subjects."

Martin, the son and grandson of coal miners, now teaches illustration and graphic design at the Mingo Career and Technical Center, in Delbarton, West Virginia, not far from where he grew up. A former animator at the Walt Disney Company, he might well have followed the family tradition of long days in the mines.

"I used to envy the students in the gifted class," he says. "School always seemed easy for them, and they excelled on the standardized tests. I feared those tests because they made me feel inferior. Because I wasn't talented in math and reading skills, I figured I wasn't smart."

Last Best Hope

"I had one hope," he says, "and that one hope was the arts. I loved to draw and communicate every feeling or emotion with a pencil and a sketch pad, and I felt like a genius in my own artistic world."

Without much help from teachers, Martin recognized his own talent and was able to find success as an artist and educator. But his unhappy school experience has made him determined to help creative students who have trouble in their regular classes.

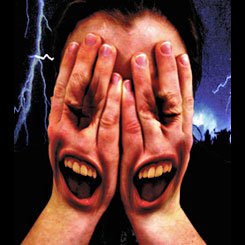

Martin provides both aesthetic and practical help. He constantly emphasizes the need to put together portfolios using digital tools, so that students have visual résumés to enter contests, move on to college, and work in the graphic arts. On this page are examples from portfolios assembled by several of his recent students, portfolios that resulted in college scholarships for each. As Martin notes, "In the past three years, I've helped my students get more than $1 million in scholarships."

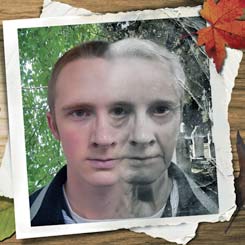

Brady Fields barely had a 2.0 grade point average in high school, and he seemed destined to drop out. But, as Martin says, "He fell in love with the arts and found a way to communicate without saying a word." Martin encouraged Fields to enter several art contests; among his accomplishments are the design for West Virginia's license plate.

This artwork won a 2006 Congressional Art Award, enabling Fields to represent the state in the annual Congressional Art Competition. Upon graduation, he had four scholarship offers, and he is now a major in illustration at the Columbus College of Art & Design, in Columbus, Ohio.

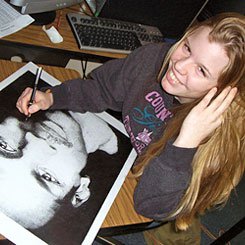

Staphaine Staley was someone Martin describes as "very fearful of taking tests," so much so that she needed to be in a room by herself when being tested. Encouraged to put together a portfolio and enter art contests, she began to win prizes, and with that, Martin says, "her confidence increased in other courses." When Staley graduated, she had her choice of several scholarships, and, like Brady Fields, she studies at the Columbus College of Art & Design, majoring in animation.

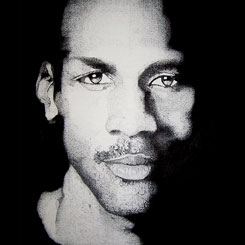

Michael Barry was a class clown, with no idea what he was going to do with his life after school. "He would show up at school for two days," recalls his teacher, Doug Martin, "then not be there for the next three." Many teachers predicted that he'd never graduate, but in Martin's class, the teacher says, he was "brilliant, turning out incredible art on the computer." Once Barry began focusing on his talent, he won a National Art Scholarship and, according to Martin, was awarded more scholarship money than the class valedictorian. Today, he works as a graphic designer at the Logan Banner, in Logan, West Virginia.

"When I was in high school, I can remember wondering desperately, 'What am I going to do for a living?'" Martin says. "I want my students to have the answer to that question."

Owen Edwards is a contributing editor for Edutopia and Smithsonian magazines.