Lessons from the Mall: A School with a Commercial Aesthetic

Turn your school into a marketplace of ideas.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Any educator walking through a well-designed mall will see kids of secondary school age who are far more actively engaged with their surroundings than when they're in school.

A large part of the appeal of a mall is that there is no obligation to do anything other than hang out, see friends, eat, window shop, and enjoy the show. In most American towns, malls have replaced the town squares and main streets, places where teenagers congregated in the Back to the Future era. And clearly, buying a T-shirt at the Gap is easier, and more immediately gratifying, than grappling with the theory of quantum mechanics or the rigors of iambic pentameter. But there are lessons to be learned from the modern shopping scene. In design terms, some of the calculations of mall planning can be replicated in schools, whether for new construction or renovations, with significant results.

Decoding the Design

Malls are machines for making money; they are intended to entice and captivate. The arrangement of goods in display windows and spilling out of shop fronts, carefully lit for maximum allure, is a specially calibrated invitation to invite us into that shop. The eye-catching signs proclaiming "Sale!" or "Bargain!" generate more interest. The mere presence of so many stores side by side means we're guaranteed to find something we like, somewhere, sooner rather than later. The mall is like one big, craftily designed signal to come in and hang around.

Typical high schools rarely entice and captivate. Students are there by decree, so no invitation is deemed necessary. Classroom furniture is usually standard issue and rarely comfortable, though teachers often do what they can to make their classrooms more appealing. And outside the classroom, there's rarely any furniture at all. Walking into a school can't be the same as walking into Abercrombie & Fitch. The store shouts, "Buy!" and the school says (hopefully) "Learn." But if a school is simply a place students want to get out of as soon as possible, it has to be considered a design failure.

Malls and schools have one common feature: They provide space for young people to be together, to talk, to play, to socialize, and to exercise some independence. There was a time when all this took place downtown -- in town squares, at soda shops, in parks, and on playgrounds. As many town centers atrophied, the mall rose in importance as a social scene that met the same needs. School architecture typically prevents rather than supports social interaction. Between the teacher-focused classroom space and the unfurnished, uncomfortable common areas, social interaction occurs despite, rather than because of, the school's design.

Merchandising 101

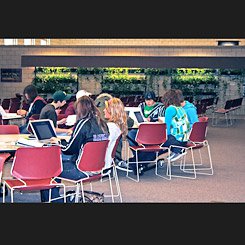

We can learn at least a couple of lessons from the obvious attractions of shopping malls. First, we can pay closer attention to the concept of invitation. To get guests to come to your party, you should create settings that recognize adolescents' need to be social and that respect them as social beings. This can be done, for starters, by setting up several small chair-and-table groupings in democratic -- not teacher-controlled -- spaces throughout the school. The idea is to invite positive social interaction, rather than to ignore or try to stifle it.

In resource centers, libraries, and other sites throughout the school, we should think like retailers, using enticing merchandising techniques to showcase students' work. This means using audiovisual equipment for slide shows and video loops, as well as creating traditional paper-based arrangements. It means celebrating the process of creation and learning as well as the final product. Just as hair salons, for instance, show passersby their hairdressers via windows and open doors, we can make the sites devoted to learning more visible, creating interest by letting others see the students at work.

Taking the concept of invitation a step further, we can work to develop a culture of student entrepreneurship or control. If students have a vehicle for inviting each other to participate, as collaborators, artists, writers, campaigners, buyers, or sellers, teachers no longer have to provide all the enticements for participation. When schools learn the lessons of mall motivation, both students and teachers benefit.

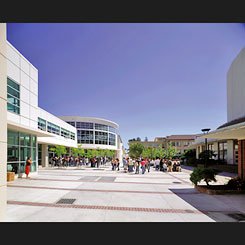

At the School of Environmental Studies (SES), in Apple Valley, Minnesota (known to its students and teachers as the Zoo School because it's next to the Minnesota zoo), the project-learning curriculum requires students to present their work both to small groups and in larger forums. When you enter SES, you are immediately in the public forum, café, and presentation space -- the agora of learning. Look up, and you can see a second-level "street" leading to four student houses of a hundred students each. The transparency and the physical and acoustical connections present in a shopping mall are evident here, with none of the chaos and failure associated with the open classrooms of the 1970s.

Many of the key spaces at SES are large, with minimal partitions, making them adaptable for different uses: The forum might be used for a formal lecture in the morning, lunch at midday, and an interactive meeting in the afternoon. But not all the spaces are community spaces. Each student has his or her own workstation, and these are arranged in groups of ten, providing the same open feeling as a mall food court but with a pedagogic, rather than caloric, purpose. Ten such groups of ten are arranged around a centrum, or open common area, which is like a courtyard off a main street -- or a section of a mall. Walk through the centrum, and, instead of various products, you will see a tremendous variety of educational projects.

Rules of Engagement

Beyond the opportunities to shop till you drop, certain basic elements make malls physically and psychologically appealing: openness, light, flow, and choice. These elements have been known for centuries, expressed in the plazas, arcades, and atria of European shopping areas and the village greens of American towns. Malls have simply adapted these customer-pleasing aspects; they can work just as well when the consumers are students and the product is learning.

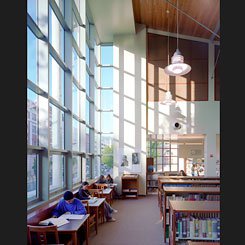

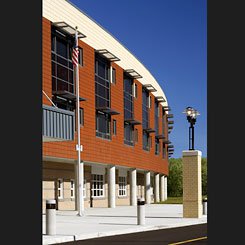

Berkeley High School, in Berkeley, California, and West Auburn High School, in Auburn, Washington, have such literally enlightened designs. In both schools, a soaring sense of possibility is symbolized by long sight lines and a liberating sense of space, plus flexibility similar to that at SES.

In the commercial environment, many shops are completely retrofitted every few years. In contrast, most schools are finished with expensive and change-resistant materials, such as painted concrete block or polished brick, meant to be durable for half a century. This apparent permanence seems a virtue to administrators, because school construction is ever more expensive, and funding for new schools is always hard to achieve. But it doesn't take a large budget or a new building to create the kind of setting associated with a lively marketplace. Features such as moveable walls, easily repainted paneling, and temporary display spaces can make minor and consistent retrofitting inexpensive. Students can only be energized by such visual freshness.

How To Do It

We don't need to wait for renovation or a new building to incorporate the secrets of the shopping mall into our schools:

- Pilot programs that invite students to take greater charge of their learning (mimicking the mall's aura of empowered decision making) can be created and tested quickly. Clearly, teachers and administrators can't cede responsibility for major learning decisions, but the more students can buy into the curricula, the more motivated they'll be.

- The spaces required to support more student-directed projects and displays and more informal gathering can often be created through rapid, low-budget remodeling, sometimes by just a simple placement of furnishings. At school, less is not always more: Most schools contain dead space that can be rejuvenated with a little creative thinking, no matter how limited the budget. Placing an interactive display amid round tables with comfortable chairs and shading umbrellas (more for the encompassing effect than any practical purpose) and adding a juice machine can make a school seem more user friendly than the old institutional sparseness did.

- In new construction or substantial renovation projects, placing power outlets near public tables, allowing students to do assignments free of the confines of classrooms or the library, can free up thinking and creativity. This is the indoor equivalent of the time-tested idea of taking classes outside to sit under a tree for a welcome change.

In the end, schools are places for learning, not shopping and hanging out. But a little mall magic can make a big difference in making young minds more receptive.

Randall Fielding and Annalise Gehling are architects at Fielding Nair International, in Minneapolis.