Straight Shooting: Depicting Their World with Photography

Foster-care kids explore their environment and themselves through art.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

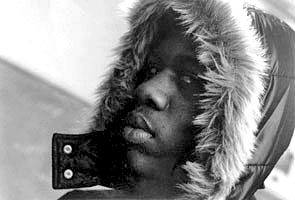

Six years ago, Mia Harris ran away from her group home near Sacramento and headed west. Like so many runaway kids -- many of them transgendered, like Harris -- she landed on San Francisco's Polk Street and started hustling and doing drugs. Recalling one of her recent photographs, Harris describes a tranny girl much like herself, looking down at the ground: "She wants to get out of this, wants to be free, but it's all she knows."

Harris did get out of that life, thanks in part to San Francisco's Larkin Street Youth Services, and very much into a new pursuit: photography. She has spent the last two years training as a photographer with a program called Fostering Art, a project of the national organization A Home Within, which provides emotional support for kids in and out of the foster-care system.

Harris has learned to handle a camera and develop photographs, but her new life -- a full-time job she likes, sobriety, her own apartment -- illustrates some broader lessons learned. "I learned that I can hang out with individuals and not be high," she says. "I learned that I can hang around a person with more knowledge than me and learn something without getting an attitude. I'm normally really shy, and now, I can express myself."

Those lessons are what Fostering Art is all about, says Toni Vaughn Heineman, a clinical psychologist and Fostering Art's executive director. Heineman has devoted much of the last ten years setting foster kids up with practicing psychologists who provide long-term pro bono care as part of the Children's Psychotherapy Project. In 2003, she launched Fostering Art. Heineman recently spoke to Edutopia.org from Sonoma, where she was taking a much-needed weekend vacation.

Your primary work with foster-care kids has been providing them with high-quality psychological care. What inspired you to start an art program?

What we hear from all the research done with adolescents in foster care is that they've just had it with psychotherapy. And, given the number of therapists many of them have had, I completely understand. What they say they want are two things: They want mentors, and they want art programs. So we started Fostering Art in response to their stated wishes to have some way of self-expression that is different from psychotherapy.

But also, most people don't know much about the foster-care system. And so we see Fostering Art as both a window into the foster-care system and a window out of the foster-care system. If these young people can produce works of photography that move you, that tell you something about their inner world and how they see the world, then that's much better than my sitting down and writing a paper about it.

What's the difference between Fostering Art and an art class these kids might get in school?

One of the things we can do as a result of being community based is to make rules about things that are important and ignore rules that aren't important. We couldn't care less about how the kids dress. But we do care that they are respectful of each others' feelings and property. And if you have a high school and you have to deal with 500 kids, you have to have more rules than that. But if you have a really small group where everyone knows each other, the rules can be internalized rather than externally imposed. At the beginning of each academic year, the kids participate in laying the ground rules for the class.

What about the foster-care experience might make art so important to these kids?

One of the things that's really important about this program is giving kids some control over what they choose to expose or not expose. For kids in the foster-care system, there can be so much confusion about what's private and what's public. Everything about their lives is protected because of confidentiality, and then, at the same time, it feels to them as if anyone at the group home can go in and read their chart. So this gives them an opportunity to decide, how much do you want to show people about your inner life? Do you want to put some boundaries around that?

Another thing is that Fostering Art establishes a peer network. It's not just individual tutoring in photography; they meet other kids who have had similar experiences. And I think that's one of the things that's very special about this -- that sense of safety, of shared experiences. They know what it's like to be living with other people's parents, or in a group home, at the age of twelve or thirteen or fifteen.

One thing that can be great about project-based-learning situations like this one is that kids develop skills without such an emphasis on the "learning" part of it. What are some of the hidden or unexpected lessons Fostering Art kids take in along the way?

They develop an idea that everybody makes mistakes all the time and that sometimes your mistakes are your best photographs. I sat in on a class where they were showing some Diane Arbus slides and reading some of her words; Arbus once said, "I never take the picture I meant to take." I think that's really important -- the idea that you may have some picture in your mind, but the photograph you take will never match the picture in your mind.

They're learning how cameras work, how to talk to each other, and how to control their impulses. One thing the kids talk about a lot is developing a sense of patience. I have not had a single kid who said, "I'm going to take this course so I can learn to be more patient," but what they say is, "I've learned to make mistakes, and it can be OK."

And then there are other skills. For example, we have this upcoming photography exhibit, and how do you talk to people about your photographs? How do you host an event? There are a lot of people here who are complete strangers, and they're going to want to talk to you. What are you going to say?

That's not so unlike, say, going to a job interview.

Exactly. And you don't have to answer every question someone asks you. How do you politely decline? Maybe no one has told them that they are allowed to say, "That's really none of your business."