Crime Seen: Students as Investigators

What’s more fun than unraveling a mystery in the classroom?

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

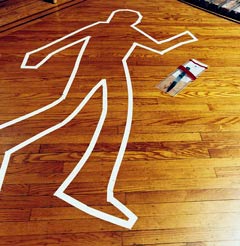

When Kevin Jones's advanced biology class arrived at Las Vegas High School, in Las Vegas, Nevada, on a recent Thursday morning, they discovered that vandals had broken into the school cafeteria the night before. The local police department's crime-scene investigator was already nosing around, trying to make sense of the wreckage. A talented gumshoe, no doubt, but he still needed the students' help to crack this crime.

They got to work, and the thirty eleventh and twelfth graders meticulously combed the cafeteria for clues, examining a cut gas pipe, scattered fingerprints, a spattering of blood, and even vomit left at the scene. In the following weeks, the students tested and analyzed the evidence, learning about DNA, cell structure, and scientific inquiry along the way. Ultimately, they deduced the culprits -- a local gang.

Unsettling stuff, if not for two points: The crime never happened, and the gang doesn't exist. Jones is one of more than 30,000 teachers to register for Court TV's Forensics in the Classroom (FIC) program since its inception three years ago. By downloading any of the five free educational units -- each encompassing a mystery and multiple scientific and procedural experiments to solve it -- science teachers now have a way of bringing standard biology and chemistry curricula to life.

"The biggest thing the kids get from it is learning to apply the scientific method, use reasoning skills, and make judgments," Jones says. "It also reinforced topics we had already covered in class, like enzymes, endothermic and exothermic reactions, and chromatography."

Forensics is usually equated with dead bodies and violent television shows, but Court TV has devised mysteries that are often less gruesome but just as engaging for students. One high school-level unit, for instance, investigates a teen who accidentally totals her parents' car; a middle school caper involves a dognapping.

The projects are reading intensive, including a thirty- to seventy-page packet per unit, and staging the scenes requires some time for preparing the crime scene and gathering materials. Each unit, however, can easily be adapted to various degrees of involvement. Teachers can simply read the unit material as background for performing the experiments or go all-out by trashing their cafeteria and enlisting the aid of local police to create a convincing setup. Each download provides specific instructions and tips on how to simulate each aspect of each crime, such as where to buy raw calf liver or how to make a footprint casting.

The American Academy of Forensic Sciences collaborated with Court TV to launch the program and with the National Science Teachers Association for its two recent additions: "It's Magic," the unit for middle school classes, and "The Cafeteria Caper."

FIC is the first free program of its kind, which uses forensics and mystery to meet national standards for secondary school science programs. Las Vegas teacher Jones says he was initially skeptical of the program, as free units are often disappointing, but his students loved "The Cafeteria Caper" so much that he's started teaching the unit every year. His take: "It makes science real."

Says Court TV spokesman John Domesick, "Usually, these experiments are taught in a vacuum, but this program gives them a way of relating to the material. When the students are doing an experiment on fake vomit, they know why they're doing that experiment on fake vomit."

Get Started

- For examples of local camp forensics programs for students, check out Fairmont State University, which runs CSI camps.

- Syracuse University’s summer forensics program for high school students.

- Check out the academy's "So You Want to be a Forensic Scientist" page