Common Dreams: Turning Empty Space Into Inspiring Classrooms

When space seems limited, all it takes is a little imagination and a lot of local input.

Your content has been saved!

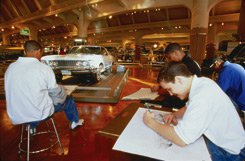

Go to My Saved Content.Credit: Steven Bingler

Architect Steven Bingler is the founder of Concordia, a planning and architectural-design firm in New Orleans. Bingler, who specializes in public buildings, especially schools, designed the Henry Ford Academy's unique facility on the campus of the Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village. Bingler has developed tools and strategies for making the design and building of learning environments a community-wide process.

When you're starting a project, how do you engage the community?

It's a long-range, hands-on, very participatory process; the community actually gets involved in identifying needs and assets. It's a very collegial kind of exercise -- one that takes place every month. It doesn't just happen once and then it's gone until the next bond referendum -- the process must be continuous and sustainable. The outcome is not just a new school or a new site but a stronger bond within the community.

We also try to get students involved. Kids are important because they don't yet know what doesn't work. A lot of other people have been there, done that, and it didn't work. Kids are the ones who haven't had that experience yet, so you can get good ideas that almost couldn't have come from an adult.

How does the process get going?

First, the community must identify assets that can be used for education, so we give people cards that they fill out to pinpoint whether a particular building or program is a cultural, social, economic, or educational asset. Then we build maps showing their locations in order to make decisions about where a school should be located. If we can put schools in places where a number of assets already exist -- libraries or recreation areas or YMCAs, that kind of thing -- then schools will become more a part of the community, and the community becomes more a part of the school.

Give us an example of the process in action.

In Dearborn, Michigan, the asset identified was the Henry Ford Museum itself. In Littleton, New Hampshire, the primary asset was empty space downtown. One of the things foremost in everybody's mind was the notion that if they already had an asset, they didn't have to build one. It turned out there was a lot of empty space on Main Street, mostly in the basements of the stores that faced the river, so there was all this empty space with a beautiful view, and it wasn't much of a stretch to put some of the school activities in these spaces.

What happened?

A number of projects evolved. For instance, the manager of the local general store had problems handling his Web site, so he and a teacher at the high school got together and decided it would be a good idea for the kids to help with the store's Web marketing, and they moved into the basement of the store. They renovated the space and brought in all their computers, and now they're managing the Web site.

Then, the president of the bank across the street saw what was going on and said he had some extra space as well. Next thing you know, a technology program that was at the high school has relocated to the bank. And, there was an empty space in the basement of Town Hall, so a whole environmental-studies program from the high school was relocated there.

At the end of the day, we have a completely different way of thinking about what a school is and recognizing that needs don't always have to be filled in the traditional way. Those three classes that moved to Main Street also opened up three empty classrooms at the school. Building new classrooms would have cost $100,000 each.