Crafting Professional Development for Maker Educators

Professional development for maker educators should introduce the materials and methods involved so that the teachers understand what students can learn from making.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Future-ready librarians are transforming traditional school libraries into bustling makerspaces where creativity and learning go hand in hand. The maker environment has the potential to teach our students to work collaboratively in ways that our curriculum often does not. Many of our students leave school lacking the abilities to solve problems, work in groups, act as leaders, and deal with failure because these skills aren’t covered in the curriculum. The good news is that these are all skills that can be gained through collaborative making and participatory learning in a makerspace. I find that combining making and research is beneficial to students because making is inquiry driven.

When you start out embedding making in the curriculum, it is essential to share with teachers the relevance of making as problem solving and the importance of process so that they don’t end up with glitter catapult assignments or extra crafty English language arts assignments that turn out more like craft experiments than true project-based learning. Sit down with teachers and look through the curriculum for places where a hands-on project could create learning across disciplines.

Whether you are teaching librarians or teachers, your professional development needs to get all educators to understand that the process and meaning a student gets from making are the most important aspects to making and education. The final product may be faulty, and that’s okay. At my campus, I work on explaining to all of our students that persevering after failure is what leads to innovation. Making stuff is cool, but the real learning happens from the meaning you get from making.

Crafting excellent maker professional development should focus on process and creativity, hands-on learning, documentation of process, and reflection, all while helping educators make a reading-writing connection with making. All of those qualities help students in their documenting and reflecting on learning, as well.

My Maker PD

What follows is an example of maker professional development that I lead for librarian educators. As a way for librarians to document their learning for the day, we create maker journals (inspired by Maker Ed) to build in time for reflection. (I use the same journals for student research.)

We make books out of scratch paper with construction paper as the cover. I share examples of other handmade notebook covers made out of upcycled materials (like cereal boxes and poster board), and then we get to the important work of filling up the notebooks with learning.

Exploring and Analyzing Maker Lingo

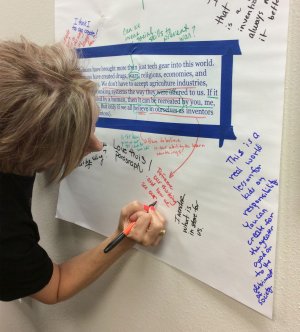

To start the day, librarian educators explore Jay Silver’s article “Invention Literacy” by using a write-around text-on-text activity I discovered on Buffy Hamilton’s blog. After reading Silver’s article, the librarians analyze, reflect on, question, and add to it by walking around the room and writing their thoughts and opinions on giant pieces of paper.

In the workshop, we also spend time together defining making, tinkering, prototype, iteration, design challenge, and design thinking as a way of exploring the terminology. It’s important to remind participants and leaders not to define making too narrowly. After group gallery walks and discussion, the librarians write new definitions in their own words in their handmade maker journals to reflect on this new thinking.

Tinkering With Projects and Materials

The next step is to get practice with maker tools. Teachers and librarians, like their students, need hands-on experience with maker tools and with playing to learn as that helps them build creative confidence.

Documentation and Reflection

It’s easy to skip this next step; however, doing so is detrimental to incorporating a long-lasting makerspace in your school. One key to learning through play is to document and reflect on learning as makers go through the process. I’ve recently added having my participants draw nontechnical or technical drawings of materials because of a conversation I had with Mark Barnett. Mark has his students create technical drawings just like an engineer would when designing prototypes. I find that by drawing the materials, the educators familiarize themselves with the tools in a more intimate way and start to assimilate important information about each maker tool.

To aid reflection, I borrow a prompt I learned from d.lab coordinator Patrick Benfield, who has students test, play with, and push the boundaries of materials as they create material libraries in their maker journals. He asks his students, “What is possible with this?”

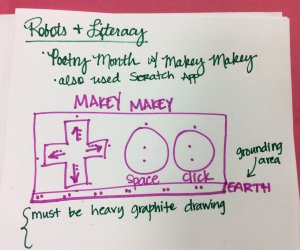

So now, after educators in my workshops play with Makey Makey or paper circuits, they spend some time reflecting in their journals on the possibilities they see with their new tools. “What is possible with this material? How can we make curriculum connections? How can this be a great learning tool?”

After Reflection

It’s important for teachers, librarians, and administrators to see examples of these materials being taken further. After play and reflection, I share concrete examples of inventions and creations my own students have made either in their free time or during their Invention Literacy Research project:

- Hack Halloween with littleBits

- Wireless littleBits car

- Invention Literacy Research: Makey Makey piano, littleBits lamp, littleBits tank

Next Step?

After your teachers get comfortable with making and tinkering activities, follow up a few months later to see how well they are connecting activities to standards. See where they need more help and offer support to facilitate a long-lasting makerspace.