‘You Can’t Lead on Empty’: On Supporting Staff With Vicarious Trauma

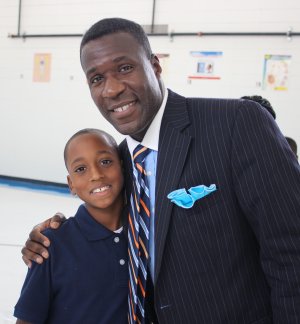

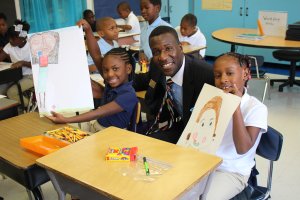

Dr. Art McCoy, superintendent of the Jennings School District in Missouri, explains the impact of vicarious trauma on staff as they support students.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Descending from three generations of ministers and church pastors, Dr. Art McCoy remembers growing up with “a passion for helping people, healing hurt, and transforming minds”—but he was determined to take his passion “beyond the walls of a religious institution.” For McCoy, a school building became his church.

At 18, he was the youngest certified teacher in his home state of Missouri, and at 33, he was the youngest ever and first African American superintendent of a local district in St. Louis County. The early years of his career were a crash course in the challenges of school leadership. In addition to learning the ropes of management, he regularly witnessed the toll that adverse childhood experiences took on the minds of his students—and the staff that supported them.

“I’ve had students who have experienced major trauma,” says McCoy, who for the last five years has served as superintendent of the 3,000-student Jennings School District, where 100 percent of students are on free and reduced-price lunch and 98 percent of students are African American. “When I go into a school building and tell the whole student body, ‘Raise your hand if you have a loved one in jail,’ 80 percent of hands go up. I say, ‘Raise your hand if it’s your brother, your sister, your mother, your father,’ and 70 percent of hands are up.”

As he navigated his career as an educator, vice principal, assistant superintendent, and superintendent in eastern Missouri, trauma continued to impact his school community. One year, he attended the funerals of seven students, and in 2014, a former student, Michael Brown, was fatally shot by a Ferguson police officer when he was 18 years old. Students regularly toiled with poverty, racism, and toxic stress—and other circumstances beyond their control.

But McCoy learned that when schools put the right systems in place, their success is “not defined or confined by zip code.” In recent years, the district has achieved a 100 percent graduation rate with 100 percent career and college placement for students. McCoy credits this success, in part, to wraparound supports for students—and crucially for the staff—that prioritize their social and emotional wellness and mental health. Since 2016, McCoy has raised approximately $2 million in private funds annually to support numerous health and wellness initiatives within schools.

Edutopia sat down with McCoy to discuss mental health, creating support systems for his staff, and making space for educators to unpack secondary trauma.

EDUTOPIA: Data suggests that one in every three Black children in the United States has been exposed to between two and eight adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Serving a predominantly Black student population, how do you see this data impacting your district?

MCCOY: For generations, there have been several epidemics that have impacted our students. One is the adverse childhood experience of having friends perish all around you. St. Louis City is the murder capital of the United States, and that is a major epidemic that our students have faced for a long time. Our students are familiar with students’ deaths and have experienced the deaths of their loved ones.

Secondly, there’s a high degree of violence in our silence. A lot of people are struggling silently with mental health issues. We were the first school in St. Louis County and city to come back in person in July of 2020. Ultimately, we believed our children needed someone to turn to and somewhere to go when it was a really difficult time for everyone. If there was one student that needed us, we would be open.

EDUTOPIA: And how does teaching and serving this student population affect your staff?

MCCOY: It takes a committed person to educate in an urban environment—particularly in an environment with nearly 100 percent of any type of population, especially African Americans. We have to educate as if our life, our legacy, and our liberty depend on it, because they actually do. You must be committed to the children. You must do for the child what they need.

The question that a student shared with me was, “Who do I turn to when I can’t even turn to the person who gave life to me?” And the answer is the youth should turn to me, to educators; to mandated reporters, to social workers, to first responders, to the adults in their life who are around them, care about them, and love them.

Yet supporting students can literally suck the life out of you, the spirit out of you. And that is my best description of what secondary trauma is. It’s the impact of literally giving your fuel to another soul so that they can go on another day and live in a brighter way.

School leaders have to remember staff need to refuel too. You can’t lead on empty. You need leaders with a perspective that say to teachers that “it’s OK to not be OK.” They should be on the lookout for drastic mood swings or outbursts among staff; isolation from peers, meetings, and projects; overly harsh reactions to students or detachment from students entirely; excessive judgment of parents’ situations; and burnout in the first few weeks after a break from school as signs staff might have secondary trauma.

EDUTOPIA: How did you come to the decision that it was important to provide staff with mental health services?

MCCOY: After establishing programs for the parents and after establishing clinics for students, it was clear that we had left out the staff. Our corporate partners gave the facilities to our staff to do monthly happy hours with a therapist and to have peace circles off the school campus, so I set up happy hours at local country clubs.

We heard the feedback from our staff, “This was amazing. I needed that. And I need this multiple times during the week.” I didn’t take that lightly. I didn’t laugh. I thought, “Hmmm, multiple times in a week.” So that seed was planted.

Seeing the popular demand, it became clear that staff needed more than just one session with somebody that was not their supervisor. We needed to make this an embedded part of the system for our success. After using Alive and Well (a Missouri-based nonprofit organization dedicated to addressing the trauma experienced by residents) for staff training and group therapy sessions in 2015, 2016, and 2017, it was evident that we needed to use district funds to hire therapists to support staff even more.

Secondary trauma is a very serious issue. It was incumbent upon me as a leader to authorize the hiring of two therapists specifically for our staff only that were separate from human resources and separate from any type of health care plan. They’re solely dedicated to walking through the schools and being on call 24 hours a day for any staff member who is suffering from secondary trauma or trauma in their personal life, while trying to sustain a successful professional life.

EDUTOPIA: What’s the risk if we don’t address secondary trauma among staff?

MCCOY: Emotions can kill you softly. How do you magnify, lift up, and help an educator to be successful? You empower them to be mentally agile, mentally strong, physically strong, and provide the culture and climate that says, “You’re home and home feels good, even in the midst of pain.” When nothing else helps, love lifts students, staff, parents, and your peers—your colleagues—through tough situations.

People don't care what you know until they know that you care, so let’s make sure that [educators] know that we care every day. Let’s make sure the system builds in caring in a greater way than we did yesterday. We can see each other, support each other, be sufficient, and have success.

But that’s only possible if you really [care about] your people. And this is the best way to serve: to be in tune with how your staff are doing today. Ask: How they are feeling? How has their mental health been? How has home been? What can we do to support you?

EDUTOPIA: Is there an end goal? Will the work ever end?

Already I see an incredible amount of willingness and action among staff to talk about how they are doing. And they’re not just talking about it—they’re making it a part of every lesson, every activity, every meeting, every structure: How do you feel? Did we honor you? Did we honor all voices? Do you feel lifted up or do you feel drained? Do we need to pause longer?

The wraparound services have become robust, but you just have to keep building to make [them] bigger and better. My goal is to do this for even more districts: to support other states, to make sure that they have the organizational infrastructure surrounding them to have the wraparound supports and services and mental health guidance that they need.

But administrators must be much wiser about the mental health of all staff and have a list of accommodations and modifications within all policies and procedures.

Use Maslow before Bloom for all, including staff. This means that time and money must be spent on promoting happiness, emotional assessments, wellness coordinators and advocates, support groups, grief groups, and ongoing feedback and temperature checks of each individual, department, and building. This is the most important part of every day, every lesson, every relationship—“How are you doing?” comes before “What do you know or need to know?” and “How are we doing?” comes before “What do we need to know or do?”