What Summer Schools Learned About the Challenges of Reopening

Across the country, forward-looking districts used summer school to anticipate—and try to solve—some of the issues they’d inevitably face when schools reopened.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.While the global pandemic continued to wax and wane, some schools quietly piloted on-site learning for small groups of students this summer—experiences, they say, that will help inform their decisions and protocols for the challenging school year ahead.

More than 15 states around the country—including Alabama, Massachusetts, Iowa, and Oregon—authorized districts to provide in-person schooling over the summer, according to the Education Commission of the States, an organization that tracks states’ education policies. To open, summer schools had to adhere to strict health regulations that guided everything from class sizes to the minimum percentage of alcohol required in hand-sanitizing solutions. No one was obligated to attend: Staff and students volunteered to participate.

"I deeply missed being in the classroom and being in school. I saw summer school as a great opportunity to get back," said Locksley Saunders, Jr., a third grade teacher in the Title I, 38,000-student Newark, New Jersey, district.

Within the mix of districts that offered in-person summer school were schools in areas that later became virus hotspots like Miami-Dade County Public Schools, the fourth largest district in the nation, and Premont, Texas, a small, high-poverty rural district, as well as school systems in places where coronavirus cases have been few and far between.

While most of the districts we spoke to plan to return to some in-person learning this fall, many other U.S. school systems are still determining if they are returning to physical schools at all. According to a recent, statistically representative study of 477 school districts, 51 percent of schools will offer at least some in-person learning this fall, a bare majority that underscores the increasingly politicized and contentious response to the virus across the country. A July survey conducted by National Public Radio and Ipsos, meanwhile, found that 82 percent of teachers had concerns about returning to school, and worried their schools were not sufficiently prepared to implement the health and safety protocols necessary to keep everyone safe.

Other educators fear the long-term implications of keeping students—especially the most marginalized children—in distance learning any longer, and question whether they can adequately do their job from a computer. More than 15 million children, or 30 percent of students, lack adequate internet or devices to learn from home, according to a report from Common Sense Media, and many students rely on schools as a source for meals, along with health and medical services.

As educators prepare for the year ahead, what districts learned piloting on-site learning this summer may have provided a glimpse into protocols and processes that become commonplace in schools—or reveal ongoing, unresolved challenges that prevent them from reopening this year.

Getting Set Up

After getting the green light for summer school from their states, the school districts we spoke to typically offered a range of options to families and staff before going ahead with plans—an approach some districts intend on carrying out this fall, we heard.

In Joplin, Missouri, surveys were administered to parents offering several scenarios for summer school—virtual, hybrid, and in-person—to see what they preferred. More than 1,000 parents responded, with the majority expressing a desire for in-school learning, and about 1,500 students—roughly 20 percent of the total district enrollment—showed up for a range of summer programs provided at eight school sites.

Elsewhere, staff in a number of districts selectively reached out to families of students who they felt might benefit most from in-person support, such as children with special needs or students who had struggled acutely during remote learning—similar to the hybrid learning models some districts are using this fall. A June survey of 1,200 educators conducted by the American Federation of Teachers (AFT) found the majority preferred opening schools with a hybrid model if strict safety precautions were met.

In developing summer school plans, educators emphasized not only that local transmission rates should meet the CDC criteria for reopening, but stressed the value of creating protocols for every aspect of in-person schooling in advance. This planning included reworking once simple processes like walking down the hallway, taking bathroom breaks, eating lunch, using shared materials, and most crucially, perhaps, how to handle a health emergency.

“Of course everyone has fear of the unknown, and I worried about bringing something home to my family,” said Mia Alaniz, a Premont Prek and elementary school teacher, who worked in the district’s summer school. “But leadership took our uncertainties and our fears into consideration and communicated everything in advance so we knew what to expect. I felt as protected as possible.”

Buses Arriving at School

Transporting students to school sites this summer posed new challenges and added costs, schools quickly found—a worry for districts throughout the country. While some school systems relied more heavily on car drop-offs or students walking to school, others offered busing with heightened health protocols and extra staffing support onboard.

When riding buses, students were asked to sit alone in seats and leave one row in front and behind them empty. Bus drivers wore masks and maintained their distance from students, and in some locations, extra staff administered a health check and temperature screening before allowing students to board.

In Meriden, Connecticut, the 7,500-student district hired “bus monitors”—existing district employees or parents—to ride along with students and ensure they followed the safety and social distancing rules. If a similar approach is taken with transit this school year, the superintendent says he’ll need to put more buses in circulation and drivers will need to make several loops—a solution that might be impractical in districts that are especially strapped for cash or where students are separated by vast distances.

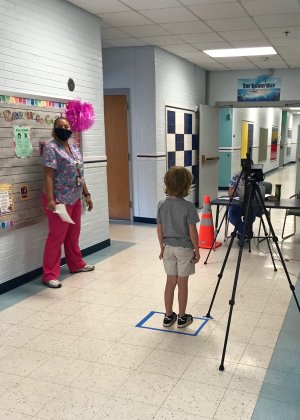

Upon arrival, students at all sites were required to go through a screening before entering classrooms, which in most cases entailed temperature checks, health questions, and hand sanitizing. In Newark, students even had their feet sanitized by stepping on a mat soaked with EPA-approved chemicals.

Though health screenings like these can provide a gatekeeping function to ward off sick students, teachers around the country have expressed concern that their schools won’t be able to access the supplies necessary—even, in some cases, running water—to conduct them for every student. "Our district has had disinfecting wipes on backorder for months. Hand sanitizer is hard to come by,” @heatherdryside wrote on Twitter in July. Summer school educators said they were hopeful that more outreach to families could help prescreen children before they arrive to lessen the load and liability for staff when more students return to school.

Health and Safety Protocols

Districts turned to local, state, and national health authorities for guidance on new health regulations, then tailored them to suit the needs of their schools, we heard.

To limit close contact between students, schools crafted new protocols to minimize congestion in common areas: Some scheduled bathroom breaks or explicitly limited use of restrooms to one student at a time; recess or outdoor breaks were contained to individual classes; and breakfast and lunch were bagged daily by food services and eaten by students at their desks or taken home when they left school.

While masks were generally required in common areas, some schools let students or staff take off their masks in the classroom, while others did not—a window into what could become a controversial issue this year that has some educators worried their job could become focused more on enforcing rules than teaching kids.

“It seems to be a very political topic in our community,” said Michelle Lesser, a principal in the Fremont R-2 district in rural Colorado, who said her state’s guidelines specify that only students 10 and older are required to wear masks. “We are ‘highly recommending and encouraging masks’ for our younger students, but won’t go as far as requiring.”

Though educators said students seemed accustomed to the new normal and adapted quickly to the school setting, there were still some difficulties. Students didn’t always wear their masks properly (sometimes they slipped below the nose), struggled to hear people talking through them, or had problems reading facial expressions. Most often, staff said students—especially the youngest—would forget to maintain space from classmates.

To help, educators recommended placing signage at key spots like the floor along hallways and giving students regular, or even scheduled, reminders. Some schools also found ways to connect the protocols to something fun. In Joplin, students were asked to hold out “eagle wings” while they walked down hallways; in Florence, Colorado, students sang their ABCs while washing their hands; and, as one really unique strategy, Premont students carried hula hoops around their waists to remind them to keep a distance from their peers.

Teaching In the New Normal

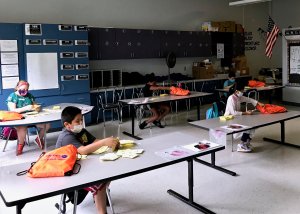

Summer school teachers said they assigned seats in advance and moved desks/tables six feet apart, which was possible with the new, lowered staff-to-student ratios that averaged 10 to 1 or smaller at most sites. To provide a similar structure with the entire student body this year, districts would need to offer a hybrid model and/or reconfigure classrooms, which may be difficult in schools with high student enrollment or that are tight on space.

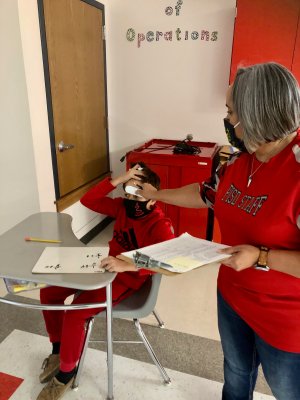

Health protocols aside, teachers said they couldn’t just pick up where they left off. Because many students had “screen fatigue” from remote learning and “struggled to get back into routine,” teachers incorporated hands-on activities, breaks outside, and plenty of time to read or journal into the curriculum. Teachers also included social and emotional lessons on topics like perseverance and mindfulness, which they felt were necessary after students spent the spring learning in isolation and under significant stress.

The hands-on assignments, in particular, involved some creative thinking. In the Fremont R-2 district and others, each student was given his or her own set of supplies that stayed on their desk during summer school. Though the materials were supplied by the district, parents, or the community, other teachers have questioned how feasible it will be to do this at scale—as many educators already spend their own cash on classroom provisions. Victoria Ryan, a special education educator in Meriden, shared that her staff felt like they “won the lottery” when they figured out how to cost-effectively (and hygienically) divvy up Theraputty for their students with special needs using condiment cups from restaurants.

Sites also adopted new rules around assignments and activities. In Premont, teachers waited 72 hours to touch/grade student assignments, while in Newark, students used digital tools like Kahoot! to engage with each other on lessons from the safety of their desks.

Challenges Ahead

Even with strong health protocols and new routines in place, things can still go wrong, summer schools discovered.

There have been isolated incidents reported of school staff catching the virus and sites having to temporarily shutter for deep cleanings. In Detroit, residents protested a summer school program claiming the district was using students “as guinea pigs,” according to The Washington Post. And though none of the summer schools we spoke to reported any major outbreaks, some camps and sports teams have seen the virus spread rapidly, especially when safety rules were not enforced.

In Joplin, where 1,500 kids attended summer classes, two elementary school students in separate classrooms tested positive for Covid-19. While a challenging situation to handle, a close relationship with the local health departments helped the district notify families early and quarantine the two classes with affected students for two weeks. Families were given the option to opt out for the rest of the program, but the summer school continued running. No other students tested positive for its duration.

Even in districts that ran successful summer school programs, there are unanswered questions as educators prepare for the fall, including how to safely scale out the best practices they learned this summer to the district at large.

“National and state guidance is ever-evolving,” said Mark Benigni, Meriden’s superintendent. “Instead of talking about all the unknowns over and over again, we should let the health data guide our current plans, but be ready to quickly transition if things change to meet the needs of our learners and staff."