Teaching Students to Read Metacognitively

A mini-lesson and anchor chart for showing early elementary students how to monitor their comprehension as they read.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Comprehension is, of course, the whole point of reading. As proficient readers read, they make meaning, learn new information, connect with characters, and enjoy the author’s craft. But as students begin to transition in their skills from cracking the sound-symbol code to becoming active meaning makers, they do not always monitor their understanding of the text as they read or notice when they make errors.

There are several categories of errors that students tend to make as they read. They may insert words where they don’t belong, substitute words as they read (this tends to happen with smaller sight words—reading the as a), make phonetic errors, or omit words completely. They may also make fluency-related errors, such as not attending to punctuation, which can lead to confusion about which character is speaking, for example.

Sometimes a student’s error will change the meaning of the text, and other times it won’t. But it remains true that the fewer the errors, the greater the child’s comprehension will be.

When students actively monitor their comprehension, they catch themselves when they make an error and apply a strategy to get their understanding back on track. Monitoring comprehension is a critical skill for both students who are still learning to decode and those who have become proficient decoders but are not yet actively making meaning while they read.

Using Metacognition to Teach Monitoring

When students use metacognition, they think about their thinking as they read. This ability to think about their thinking is critical for monitoring comprehension and fixing it when it breaks down.

When I introduce the concept of metacognition to young children, we talk about the voice in our head that talks back to us while we think and dream. We talk about how this voice also talks back to the story while we read. As we read, thoughts bubble up for us, and it’s important to pay attention to these thoughts. When we’re reading and understanding a story, we talk about how our minds feel good. When we don’t understand a story, our minds have another feeling entirely.

Mini-Lesson on Monitoring

I teach a mini-lesson that has proved effective in helping my third-grade students understand what monitoring comprehension feels like. I use the poem “Safety Pin” by Valerie Worth, which describes this common object, without naming it, by comparing it with a fish and a shrimp—and I don’t reveal the title to the students at first. (The Emily Dickinson poem “I like to see it lap the Miles” can be used with middle and high school students.)

After we read the poem, I ask, “What do you think this is about? What words in the poem make you think that? What do you picture as you read it?” The students generally say they think it’s about a fish or other aquatic animal, and I try to steer them away from these ideas by pointing out other lines in the poem that contradict that image.

After gathering their ideas, I delve a little deeper in my questions, and we discuss how their minds felt when they heard the poem. Most of them say that it felt uncomfortable not to fully understand the poem. I explain to them that something similar happens when we read and make mistakes, or read something that’s too difficult so that we don’t fully understand: Our minds simply do not feel good.

I then reveal the poem’s title and pass out some safety pins, and we reread the poem together. Many of the students find the reveal to be terribly funny. We discuss how our brains feel after learning what the subject of the poem is. I emphasize that as readers, it’s important for us to pay attention to how our brains feel so that we can make sure we truly understand what we’re reading.

Charting It

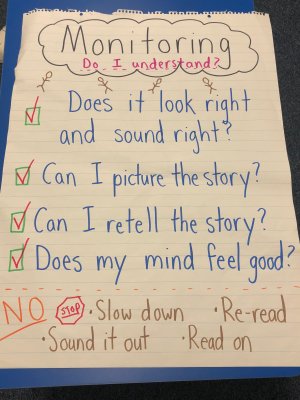

After this mini-lesson, I share with my students an anchor chart I made based on ideas in the book Growing Readers by Kathy Collins. It has the following questions for students to ask themselves as they read: Does it look right and sound right? Can I picture the story? Can I retell the story? Does my mind feel good?

The bottom of the chart outlines what students can do if the answer to any of these questions is no: Slow down, re-read, sound it out, and read on.

I have students practice monitoring with their independent reading books and a pile of sticky notes. If something doesn’t make sense, and they’ve tried re-reading, they jot a note on a sticky and later discuss what was confusing with their partners or me. I’ve found that through conferring with students about their independent reading, and giving them support and feedback during small group sessions, I’m able to guide them to develop their monitoring skills more fully.

Monitoring comprehension can be a complicated skill for some students—it requires a lot of practice, and teacher modeling is critical. But the effort does pay off.