Making Formative Assessments More Efficient and Effective

Incorporating peer review and individual reflections makes frequent, intentional formative assessment manageable, with big benefits for student learning.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Early in my teaching career, I remember shuddering a bit on the inside when someone brought up the importance of “formative assessments.”

In my mind, I was already drowning with the actual assessments in the classroom in terms of designing them and giving effective feedback—and on top of these summative assessments I now was expected to bring in formative assessments, too?

As an early-career teacher, I was already overwhelmed. So formative assessments were few and far between in the classroom.

Which was a mistake.

Looking back now, I realize two things I was entirely wrong about: First, there were ways for formative assessments to be much more efficient and effective than I initially realized, and second, a classroom built around formative assessments was much, much better for student learning.

3 WAYS TO LEAN ON FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT MORE EFFECTIVELY

1. Target a specific skill for feedback in a longer task. Perhaps one of the downsides of rubric culture has been to try to provide expectations and grading guidelines for every aspect of an assignment. This is understandable and well-intended, as students often ask for and appreciate clarity while teachers need a tool to rely upon to justify their grade.

However, the result? Teachers spend too much time trying to give feedback on every aspect of the task, and as a result, the quality of the feedback is stretched thin by its quantity, and students also are often overwhelmed by all the different notes they receive in return. (Not to mention the research around too many grades being a potential negative.)

The shift I’ve made in recent years is to remind myself that you can ask students to practice without attaching a grade to everything—and, I’ll admit, having a strong spiral notebook system is incredibly helpful with this—but also remember that you do not need to leave feedback on everything you ask students to do.

Instead, I much more frequently have students write a constructed response and then highlight a targeted focus of the day’s lesson. For example, I may have students write a response to one of our readings and then highlight their use of a skill we have just covered, such as a participle phrase or colon-introduced textual evidence.

On my end, this makes the feedback stage much more effective. I zoom in on the specific skill I wanted them to focus on and give detailed, high-quality feedback, and with the “zooming in” that feedback tends to be much more effective as well as efficient—better for me, and better for students.

2. Empower students to score themselves with peer samples. As many teachers have experienced, one of the downsides of exit tickets is the time it takes to read and provide feedback on each of them individually. Given the time constraints in our work, though, many teachers choose to assess student learning less frequently.

A strategy I lean on to still provide these formative assessment opportunities despite not having nearly enough time? Building a “feedback lesson” for the following day off of exit tickets.

The first step here is to read a handful of the exit tickets and curate a range of responses in quality. For example, if the task had a rubric scale of 1.0–4.0 points, I would be looking for one that cleanly fit into each level of the rubric. From there, I make copies either physically or digitally, removing student names and frequently creating my own version of the lower student samples to avoid a student seeing their own work receiving too many critiques.

Then, at the start of the next lesson, I create a “peer feedback gallery walk.” I walk students through the previous lesson’s exit ticket criteria and any rubric that was provided, and then students get “to be Mr. Luther”: They travel the room, usually in pairs or small groups, trying to accurately score and leave feedback on each sample.

Once everyone has completed this activity, I review the actual score and reasoning for each of the samples in front of the class, addressing any questions students might have. Then students receive their own exit ticket back and score themselves—reflecting on what they did well and also what they could have improved upon.

To be clear: This isn’t just about saving time—it is about shifting agency to students in understanding their own work and building the capacity for ownership in their learning journey as we move forward.

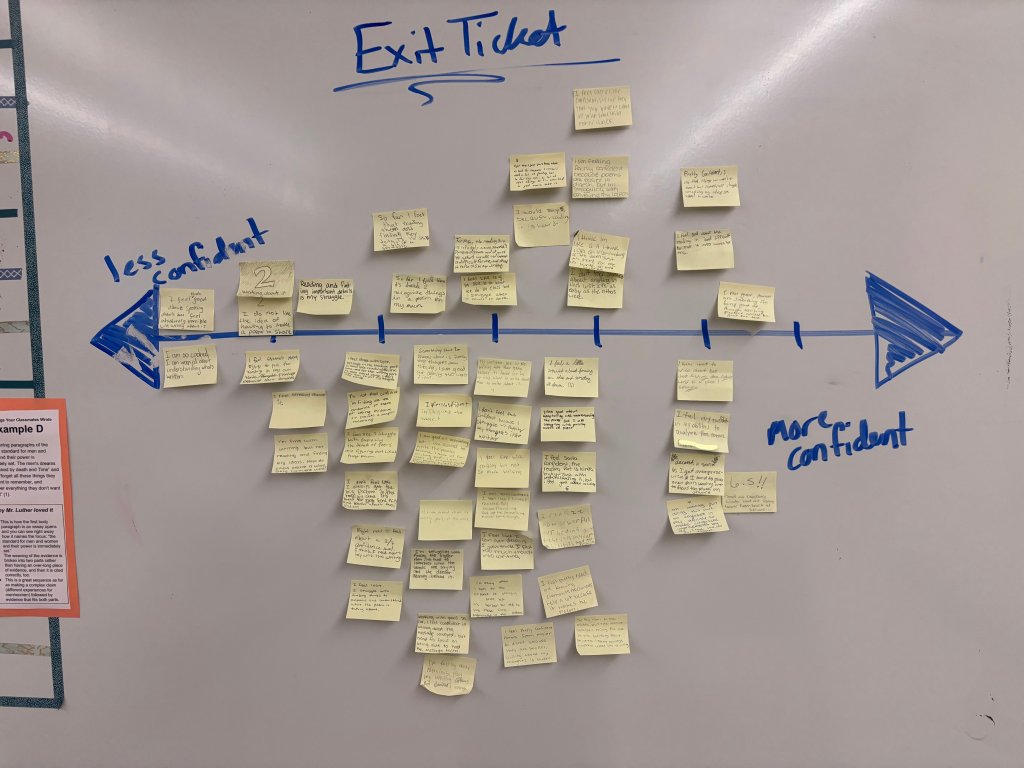

3. Utilize a student confidence reflection. Of course, it is important to have reliable methods of understanding what students have learned and where they are with the skills we are working on in class. But what sometimes gets left out? How students see themselves as learners.

This is why I try to go one step further with my formative assessments as frequently as possible by adding in a simple, final question before students are done: How confident are you in what you just did?

Usually on a numerical scale (for example, 1–5), I ask students to identify their current level of confidence and add a brief reflection of why before they submit a formative assessment.

As a result, I walk away with two things I see as critical to being my best self as a teacher. First, I have a much clearer understanding of how individual students feel about themselves with whatever our current learning focus is. Stepping back, I also get a snapshot of how I am doing as a teacher—because if students don’t feel confident about what they’re learning, I have work to do. Plus, there is a ton of value, I believe, in helping students develop metacognitive strengths around self-reflection with activities like this.

Why This Ongoing Conversation With Students Matters

In too many classrooms, assessments are where learning stops. Students do their best, they receive a grade or test score, and then we move on.

Moving toward a focus on formative assessment in the classroom opens the door, however, to an ongoing conversation around student learning. Instead of having students take a high-stakes assessment each month or so, I can build the classroom around more-frequent, more-targeted opportunities to understand where students are and communicate back to them what’s next. This is the space where I’m at my best as a teacher, and that’s why I want to continue leaning into a classroom that centers formative assessment—intentionally, frequently, and reflectively.