Helping Elementary Students Improve Their Working Memory

Explicitly teaching brain-based memory strategies can help students build their executive function skills.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.We all have those students who never seem to get it. No matter how many times we repeat the directions or how intentionally we scaffold the assignment, these students come to us and say, “What do I have to do?” Counterintuitively, the issue is not how clear our instructions are, but rather that the student’s working memory is overwhelmed. The student either is struggling to recall what they must do or is struggling to find an entry point into the assignment.

Unfortunately, most teacher training materials do not provide sufficient depth on how to navigate this issue in a classroom setting. There are techniques supported by neuroscience that can help you achieve tremendous gains in students’ working memory, improve your classroom efficiency and small group instruction effectiveness, and boost your students’ holistic development. Fortunately, we as educators can help students increase their working memory capacity, which will have tremendous impacts on both student success and classroom efficiency by explicitly teaching students about how their brains work.

Create a Toolbox of Working Memory Strategies

Working memory is one of the executive functioning skills. I call it the brain’s “triage workspace.” The brain uses this space to decide whether it should encode the new information and the new inputs into long-term memory, encode it into a plan, or discard this new information or input to make space for new things coming in. Working memory typically holds two to seven pieces of information at a time. In the education context, working memory is what allows students to recall directions a teacher gave, create a plan for what they need to do, or encode (map) a new strategy for a problem.

Below I list the strategies I teach over the course of a school year to increase my students’ working memory using the method outlined above. No one set of tools works for all students, but by giving them options to choose from, you maximize their chances for more academic and life success.

Working Memory Strategies For Directions

Repeating directions. This reinforces information, which allows the brain to have another chance to understand and retain the information, which allows it to hold, recall, and process information to improve accuracy.

Identifying what you do know in sequential order. This can help the working memory by activating prior knowledge, clarifying the task structure, and organizing the information into a logical sequence.

Describing what’s next. By narrating what you think you must do, you utilize verbal rehearsal, which can clarify or organize information and reduce cognitive load.

Writing information down. This helps to reduce the mental burden of holding information in the working memory, making it an externalized memory to reference.

Working Memory Strategies for Routines

Making associations (common routine or event). This allows the working memory to link new information with something that is already known, allowing for stronger encoding, which will boost recall.

Consistent rules and routines. These allow for less working memory usage and mental effort to remember what and when to do. This frees up the working memory for more problem-solving to support retrieval of information.

Using fingers to ID steps. This activates motor memory by offering physical and visual support to track sequential information and self-monitoring.

Using visuals. This activates visual memory to recall or code information; it takes an abstract concept and makes it more concrete for dual coding.

Working Memory Strategies for Accessing or Recalling Learning

Acting out learning. This utilizes kinesthetic memory to deepen processing and mental process of memory.

Teaching a partner. This forces students to build confidence by actively retrieving the information and explaining, which promotes recall and clarifies understanding of the information.

Visualization. This trains the brain to hold and manipulate information by creating mental images, which helps retrieval and retention of information.

Chunking information and directions. This offers the brain a way to group meaningful information (about four to seven items) by lessening the cognitive load and supports retrieval of information so that students can more accurately synthesize information.

Meaningful associations. This offers context clues to the supporting memory. It can support encoding and retrieval of information as multiple brain pathways are activated.

student Ownership of Working Memory Expansion

To effectively teach working memory strengthening and expansion, you should repeat the skill building throughout the semester. In relation to each you skill, you should do the following:

- Explain the what, the why, and the how behind the concept and how it works neurologically.

- Link the concept to what the student wants in terms of success.

- Scaffold the student’s mastery of this concept and related skills.

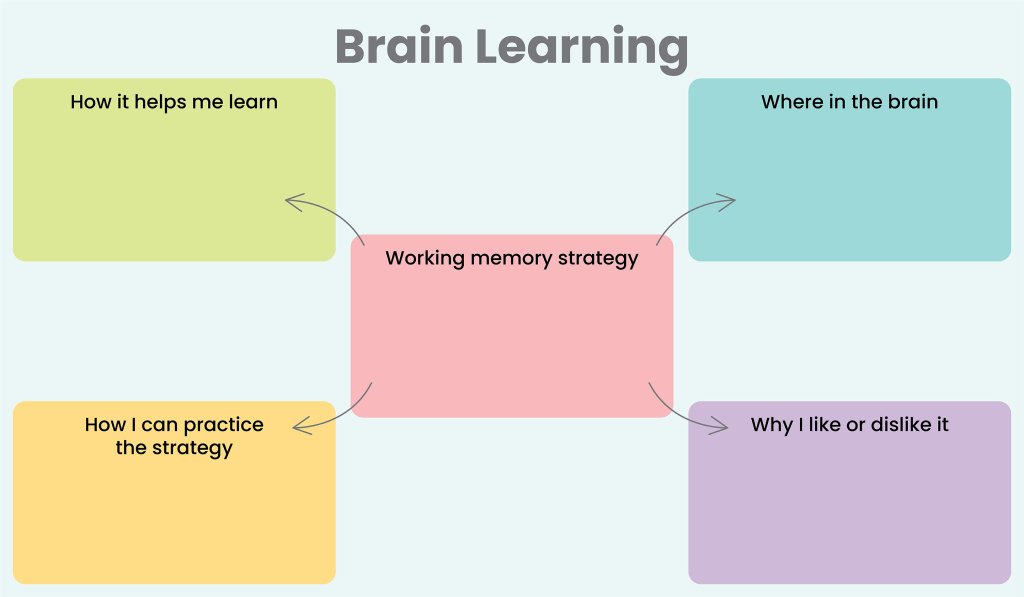

I set up time within my class called “brain learning time,” where I teach one strategy at a time. Early in the year I de-stigmatize forgetting. I explain that our brain cannot hold a lot of information at once, which is why it is easy to forget things or misremember.

I then explicitly teach each strategy by explaining how it supports our brain, and then I make sure we practice it together. One example of how I do this for a writing assignment is to explicitly give the directions: “Today you are working on revising your writing. To add details to your story: (1) open your writing notebook, (2) reread your story, and (3) find three places where you can add details.” Then, I model the strategy and say, “To support my memory, I am going to use putting fingers up to remember the steps.” After I ask students to copy me and explain this, throughout the rest of the day we practice using fingers to recall steps to help grow our working memory.

Embedding strategies throughout the day is key to helping students take ownership. For example, in math, when working on a two-step math problem, I explicitly teach how I help my brain approach the problem. I tell students that I am going to act out each step of the problem; I often pair this with a bar model after so they have a visual representation of the acting out.

Once I model it, I have students emulate me with partners during a turn-and-talk. As we discuss the approach to the problem, we tie in how the strategy of acting it out helped our working memory process the information to determine how to approach or solve the problem. We then continue the acting-out strategy until the end of the day, when we reflect on how the strategy helped improve their learning.

After I began working with my students on improving their working memory, I noticed growth academically, socially and emotionally, behaviorally, and within their executive functioning. I’m always overcome with emotion when my students show pride in how far they have come and shift from telling me “I forget” to “So I don’t forget, let me use one of my working memory strategies to help me remember!”