The New History: Teachers Learn to Face South Africa’s Past

A novel approach allows South African educators to talk about sensitive topics.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Nicola Frick's classroom is buzzing as her students sit in small groups, discussing the question looming on the board -- "What is to be blamed for the Holocaust?" The girls in Frick's ninth-grade history class at Herschel Girls' School, in Cape Town, have many ideas -- fear, propaganda, indoctrination. Also on the board in front of them are Frick's stick figure drawings of a victim wearing a Star of David, a Nazi with a gun, and a bystander looking on with large squares of cement where his feet should be. Was the bystander stuck in place? "He could have kicked the cement off," answer the girls. "He could have done something."

Fourteen years after the end of apartheid, Frick's students and their peers are navigating a new South Africa, and educators are using history to engage them in their roles in this growing democracy. Since 2003, Frick has participated in Facing the Past, a teacher-support program run by the nonprofit organization Shikaya, the Western Cape Education Department, and the Boston-based organization Facing History and Ourselves.

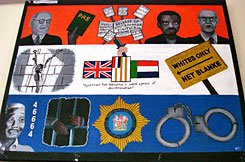

Facing the Past uses Nazi Germany and South Africa's apartheid history as case studies to get students to consider their own prejudices and identities and to think about the choices they make. It is social and emotional development, through history, for young people in a country grappling with a divided past.

South Africa's history courses today are radically different from the heavily propagandized classes that characterized the subject before 1994, when the nation's first multiracial elections were held and the African National Congress came to power with Nelson Mandela as president of the new democracy. There is now a human rights curriculum with a focus not simply on facts but also on how students should approach history, inquire about it, and understand the way it's constructed.

A crucial element of Facing the Past is getting teachers to think about their own conditioning and to confront their own history before working through this material with their students. "I think the extent to which we were conditioned by apartheid is deeper than any of us actually realize," says Gail Weldon, senior curriculum adviser for high school history in the provincial education department.

"I know how indoctrinated I was," says Frick, who is thirty. "People who are older than I am are even more indoctrinated, and that has to influence their teaching, irrespective of race. If we're not critically looking at how who we are influences how we teach, then we're just perpetuating either hatred, or maybe indifference, toward the other."

Through a series of intensive workshops, Facing the Past asks teachers to delve into their own experiences, engaging with the legacy of South Africa in a way no other professional-development program does, while remaining in the context of teaching history.

A New Kind of Teaching

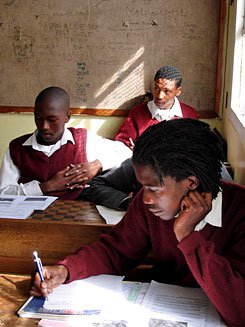

Twenty history teachers are gathered in a conference room for the first day of a three-day workshop. This mandatory workshop is the first step in their Facing the Past experience. These teachers are representative of their country, diverse in race, age, and gender, with many stories to tell. They teach everywhere -- public township schools in areas of deep poverty; formerly all-white government schools, which, despite the end of apartheid, remain largely segregated; and private schools.

For some, this is the first time they have interacted with teachers from another area or even another race. Most have not had professional-development opportunities such as this and come excited, and a bit wary.

Standing in front of this group, Dylan Wray, a former teacher and the director of Shikaya, reminds them of why they have come. "We are still a very fragile democracy," says Wray. "We have political challenges, we have an electricity crisis -- all things that potentially affect democracy. And we can engage students in these challenges through history." He explains that as history teachers, they can help shape students to become active citizens, voters, and young people who are invested in the new South Africa.

Over the next three days, and then in a second workshop and through follow-up support, these teachers will embark on a journey together, not only as a community of educators but also as learners themselves. They work through dense material on topics such as eugenics, the rise of Hitler, the causes of the Holocaust, and the experiences of perpetrators, bystanders, and victims. At the same time, they learn new methodologies and get resources to bring back to the classroom. The teachers act like students: They complete activities, work in groups, and go beyond their comfort zones.

Though the Holocaust may be far removed from South Africa, the stories from that time resonate with the apartheid era. Facing History's Karen Murphy works in South Africa and several other countries in transition, including Northern Ireland and Rwanda. "Facing the Past offers an interesting opportunity to use another story as a way to safely begin to look at your own," she says. "Teachers who might have thought, 'I'd rather not talk about apartheid' can find themselves in the moment, intensely talking about it, because they're talking about Weimar, Germany. Or they find themselves more clearly analyzing what is taking place today because they're actually analyzing another place, another time."

The old system left a significant stamp on the classroom in many ways, including institutionalized rote learning and teaching and an overreliance on textbooks. The hope is that gaining more in-depth content knowledge will allow teachers to be open to different ways of running their classrooms.

"There needs to be some training on how you teach these histories in a way that allows kids to discuss, to debate, and to think about things while releasing the teacher from being the sole provider of all the knowledge and the answers," says Wray.

Andile Yamba, a teacher at Oscar Mpetha High School, in a local township, just started the program and is open to new methods. "I think if I were to move from a traditional approach, my learners would become independent thinkers and develop a sense of their own for history," he says. "They are not just recipients of knowledge; they are active participants." Yamba is just beginning to experiment in the classroom with what he is learning in the workshops, for instance, trying new methodologies such as mind mapping to help students with their writing.

Starting with Ourselves

Back in the workshop, the group has just finished exploring education during the Weimar Republic, and now they are opening up about their own learning and teaching experiences during apartheid.

From across the room, Nancy Qavane, a black teacher, says, "If I go back, what I remember at school is riots and boycotts."

"Yes!" echoes Samantha Small, a colored woman. (Colored is still a standard term in the new South Africa for people of mixed racial descent.)

"And teachers being absent because they were detained," continues Qavane.

"Exactly!" states Rozeanne October, who is colored. "1988 and '87."

"In the classroom, relations and practices reflect the ruling class. Back then, it indoctrinated values of obedience, passiveness," says Gary Booi, who is black and now teaches at his old high school.

Nick Speelman, a colored teacher, recalled the messages he got. "Some of our teachers took it upon themselves to explain to us what the struggle was really about. And it was strange to see that some teachers were in favor of the struggle and some teachers, they sort of were against it -- not really against it, but they were trying to teach us not to be like that."

However, there are several sides to this story. "We had a problem as whites," adds Daantjie Nortje, who teaches at a dual-medium, or bilingual, Afrikaans and English government school, explaining why people didn't challenge the status quo. "We didn't make the laws, and we didn't make the school rules, but we had to apply them, and they were applied to us. There's a small part of South Africa that was teachers and students who just had to obey the laws, the rules."

Moving the conversation forward, the provincial education department's Gail Weldon asks teachers to consider the task at hand. "And as we delve into this whole melting pot of who we are, you're being asked to do something very, very different with education. Having come from the past we come from, we're now in another transition. Almost without preparation, we now have to create a generation of young people that is very different. And I think it's incredibly challenging for all of us."

Back in the Classroom

Four and a half years into the program, Nicola Frick has completely integrated the Facing the Past philosophy into her classroom. But taking the program back to the classroom is not always easy. Many teachers come from underprivileged schools. Many have students who speak several languages. Although the workshop encourages group work, some teachers find this daunting and doubt if they can get a class of sixty students into pairs or groups with limited space. Others must adapt some of the more advanced readings to their students' level.

Additionally, as the number of teachers in the program grows, the organization has difficulty doing the necessary follow-up, observing teachers in the classroom and helping them transfer what happens in the workshops into their teaching. Facing the Past is trying to increase its capacity to nurture and support the teachers it works with.

Back in her classroom, Frick continues her lesson. She asks her girls whether any of them remember when Denis Goldberg visited the school last year. During his talk, students had asked Goldberg -- who was on trial with Nelson Mandela and spent twenty-two years in prison for treason -- why, as a white person, he got involved in the struggle. Frick continues, "And he answered, 'Because that's how I'd been brought up. My parents had taught me that we have to stand up for others.' So he surrounded himself with people who helped him kick off the cement of white privilege."

Frick is determined to help her students see past their school gate. "I want students who are able to put their feet in another person's shoes and who are aware of the world beyond their front door." At stoplights all over town, unemployed, often homeless men and women sell trinkets, plastic bags, joke pamphlets, trying to make a sale or get some loose change. "I want to have students who don't just stare forward through their front windshield when somebody comes up to their car. Because if you can turn and look at the person and say, 'Hi, no thank you. I don't want one today,' that is everything. I mean, it's a human being trying to make a living. I think if they can respond like that, then that's everything."

Ultimately, those involved in the program hope this unique exploration of history will transform students, that they will come to know bias when they see it and carefully consider the choices they make, and their impact. The hope is that their students will become active participants in South Africa and the world around them.

Molly Blank is a documentary filmmaker and a freelance writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Her most recent film is Testing Hope: Grade 12 in the New South Africa. The nonprofit organization Shikaya is assisting her with film outreach.

Separate but Unequal: A Snapshot of South African Education

During apartheid, there were four separate education departments -- one each for Whites, Coloureds (those of mixed race), Indians, and Bantus, or Blacks. A decade and a half into democracy, the legacy remains, and many say there are still two separate education systems: one for whites and one for everyone else. Most schools still maintain fees, which are often nominal, but are prohibitively high at most formerly all-white government and private schools. The majority of students who are black or colored learn in struggling township and rural schools, often with forty to eighty students crowded into a classroom, and sharing desks and chairs in buildings with broken windows and scarce resources.

In 2007, the national pass rate for twelfth-grade exams was 65.2 percent, a significant decrease from where it was four years ago. Without passing these exams, students cannot go on to a university, and many find it difficult to get a job. In a country with an official unemployment rate of 23 percent (unofficially, the figure is as much as 40 percent), education is crucial. -- MB