AWOL Helps Troubled Students Make the Grade

A nonprofit group’s summer and after-school programs support a Georgia school district’s curriculum.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Dynamic Duo:

Tony and DaVena Jordan founded of AWOL (All Walks of Life) to provide a creative outlet for troubled kids.

Credit: Courtesy of DaVena JordanTony Jordan had a troubled youth. His father was absent, and his overwhelmed mother sent him to live with relatives in South Carolina after his brother was gunned down in the streets of their Washington, DC, neighborhood. Jordan was kicked out of school after school and shuttled from relative to relative before an observant principal finally helped put him on a new path, he says, one that led to college instead of an untimely death, or jail.

The principal noticed that, despite the foul language and behavioral problems, Jordan earned A's and B's. So he helped place the eleventh grader in an alternative school that could chisel away his rough edges. Outside of the traditional academic setting, Jordan thrived. Teachers countered his profanity by challenging him to master the English language and become a public speaker. Each day, they offered him support and a reminder that if he applied himself, he could make a positive contribution to the world.

Seventeen years later, he has. In 2003, Jordan and his wife, DaVena, transformed a collaborative-arts group in Savannah, Georgia, into a nonprofit arts and technology center called AWOL (All Walks of Life). The center's mission is to create opportunities for troubled youth so they can improve their situation. The program promotes individual achievement while supporting the academic agenda in the Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools with 22-week project-learning programs in four subject areas: the performing arts, film, music production, and information technology.

Setting the Bar -- and a Good Example

Whatever a student's struggles -- a learning disability, disadvantaged circumstances, antisocial leanings -- AWOL, which accepts students ages 12-22, welcomes him or her with open arms. "I'm most proud of our ability to take a kid in the midst of personal issues and put them in a healthy, family-oriented environment where they feel loved," Jordan says.

The organization gives each participant a "man-up plan" that outlines specific academic, behavior, employment, and personal-growth goals. From there, AWOL tailors the program to meet the individual student's needs. The results speak for themselves: About one in three students enter the program after tangles with the legal system, and 90 percent of those kids complete probation while in AWOL without new referrals to court. Roughly the same percentage of AWOL's 362 graduates have gone on to college, technical school, the military, or a job, says Jordan. The program's success has led to an annual increase in enrollment; this year, 152 young people are enrolled in its programs.

Savannah mayor Otis Johnson says AWOL fills a crucial need in a city in which, last year, 70 percent of students qualified for free or reduced-price lunch, a surrogate marker for poverty. "Our school population has a majority of its students coming from challenged social and environmental backgrounds, so they need much more than what the average public school can provide for them given the legal mandates of what must be taught in these schools," Johnson explains.

"We know by looking at the failure rates in kindergarten and first grade that many of these students are coming from social environments that haven't adequately prepared them for academic success," he adds. "They start experiencing failure at a young age, which does something negative to their self-image, and they begin to compensate with behavior that we don't understand, appreciate, or tolerate in the school system."

Johnson says that beyond the specific AWOL programs that reinforce positive behavior and allow young people to express their creativity, the Jordans also provide a model of marital stability that many of the young people don't see in their immediate families or in their neighborhoods. "They are a good example of what we hope these young people will evolve into," he says.

Connecting with Kids

April Hendrix, a high school special education teacher for Savannah-Chatham County Public Schools, is one of a growing number of educators and guidance counselors who refer students to AWOL. She's referred 12 students to AWOL following anger-management workshops that Jordan has led in her classroom. (Because of transportation issues, some kids did not ultimately participate.) Hendrix adds that budget restrictions and federal No Child Left Behind legislation prevent schools from starting their own AWOL-type programs.

She believes several factors contribute to AWOL's success: the staff's patience, its use of music, and its appreciation for kinesthetic learning. "They allow kids to ease into the program, instead of enforcing all of these rules," Hendrix says. "A lot of times, as a teacher, I see that students are overcorrected for things that teenagers naturally do." AWOL allows students to move around, be vocal, and socialize. "Young men especially require movement," Hendrix notes. "They may be able to memorize ten words for a few days, but if you get them moving while they are learning, they may very well learn them for life."

Hip-hop music, in particular, engages students, says Lloyd Harold, an art teacher at Pooler Elementary School and lead instructor for AWOL's sound-design program. He feels that art-related terms such as alliteration and hyperbole become more relevant when rooted in discussions about artists and styles that the kids like. Harold teaches everything from literary devices to conflict resolution while giving AWOL participants a chance to write, produce, record, copyright, and market a full-length studio album. Moreover, the program gets students out of their comfort zone and helps them develop social skills by having them work in teams that span grade levels.

"It's still an educational setting, but we deal with subjects that they are genuinely interested in," Harold notes. "Teachers are so worried about making sure kids test well that they can forget to get on a one-on-one level with the students and figure out what's going on in their lives and in their minds. Because AWOL is a creative outlet, it is easier for us to do this here than it is at school."

Roni Henderson, who runs AWOL's theater arts program, says AWOL's programming is a magnet for visual, tactile, and kinesthetic learners who struggle with rote learning. "I've taught high school English and seen those same kids navigate a public school environment," she says. "They don't fit in, and there's a high stress level. They come to us, and they can be themselves. We embrace all of their energy and integrate it into what we do."

For example, when introducing students to the civil rights movement, a typical classroom teacher might begin with a lecture or reading assignment. At AWOL, the instructors used police brutality as a point of departure for the discussion, because it is something that many of the students have witnessed. They then improvised a theater scene around excessive force and used that to spark discussion about how misunderstandings and fear can lead to the loss of innocent life. "We connected first, then put history to it," Henderson explains.

Involving the Community

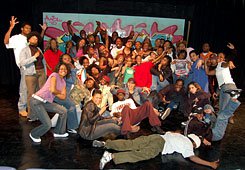

Most AWOL programs are limited to fifteen students so that teachers can offer the individual attention and differentiated instruction its participants need. One exception is the performing-arts initiative, which stages an annual hip-hop history play. Any member of the community may participate in the production. The cast of more than fifty young people and adults learns theater etiquette, conflict resolution, and performance techniques while writing, rehearsing, and performing a Black History Month show.

Ethan, a tenth grader at Jenkins High School who is in the production, says that since he began playing Marcus Garvey -- an early-twentieth-century activist who inspired many U.S. civil rights leaders -- he has started to see the civil rights movement pop up everywhere: on television, in conversations, even in class. "I might hear something in school and already know about it," he explains. "We don't just put on a play. We actually learn information about it, not just our lines."

To get into character, Ethan peppered his history teacher with questions, searched the Web for details, and pored over videos to see how Garvey spoke and carried himself. The research makes the performance more authentic -- and often a history lesson -- for the 1,200 kids the school district brings to each of AWOL's three performances each year.

Ijtihad, a ninth grader at Jenkins High School, says the confidence he's gained from performing in the play spills over into all areas of his life. He says his grades have improved so much that other kids in class now ask him for help. "In eighth grade, I had mostly Bs and Cs," he adds. "Now, on my last report card, I had two As and two Bs, and I was really proud of that."