Why Kids Should Nature Journal at All Grade Levels

A 2023 review makes a strong case that hands-on observation of natural phenomena has both academic and psychological benefits.

In 1831, a young Charles Darwin embarked on a five-year voyage aboard the HMS Beagle, tracking along the coast of South America and making stops at the Cape Verde Islands, the rainforests of Salvador de Bahia, and the Galápagos Islands. Armed with his notebook and pencil, Darwin—having just earned a bachelor’s degree studying botany at Cambridge—was eager to begin documenting the exotic wildlife of the land.

“Most people pay little attention to what’s going on around them, and do not seek to see further ahead,” writes University of Oporto biologist João Paulo Cabral. “Darwin’s curiosity, on the other hand, had no limits.”

What started as a convenient method for recording his observations—his field notes and sketches span over 300 specimens in 15 notebooks—soon became the catalyst for charting the minutiae of species diversity, as Darwin meticulously unearthed patterns that wouldn’t be obvious to the casual observer. The unique beak adaptations of the Galápagos finches, for example, paved the way for a famously era-defining breakthrough.

Today’s scientists-in-training, by contrast, “mostly learn about photosynthesis by rote” and rarely touch actual flowers in the process, according to a 2017 study. Studying the shape and function of a stamen, petal, or pistil introduces young students to textbook concepts of living systems, taxonomies, and classifications, but removed from nature, kids experience an approach to scientific learning that may curtail a sense of wonder and curiosity.

Encouraging students to wander with notebooks and pencils, paying attention to “the tiniest flowers in the grass and other bits of nature that usually go overlooked,” on the other hand, can slow them down, calm their nerves, and engage them in rigorous, purposeful academic work. “Nature journaling is an effective way for life science teachers to get adolescents outside and incorporate nature studies into their lessons,” explains high school biology and environmental science teacher Jennifer Bollich in a 2023 review, noting that it connects them to “the native plants and animals that share their spaces” and has “positive educational, environmental, and psychological effects on adolescents,” including a reduction in stress and anxiety.

Building Scientific and Cognitive Skills

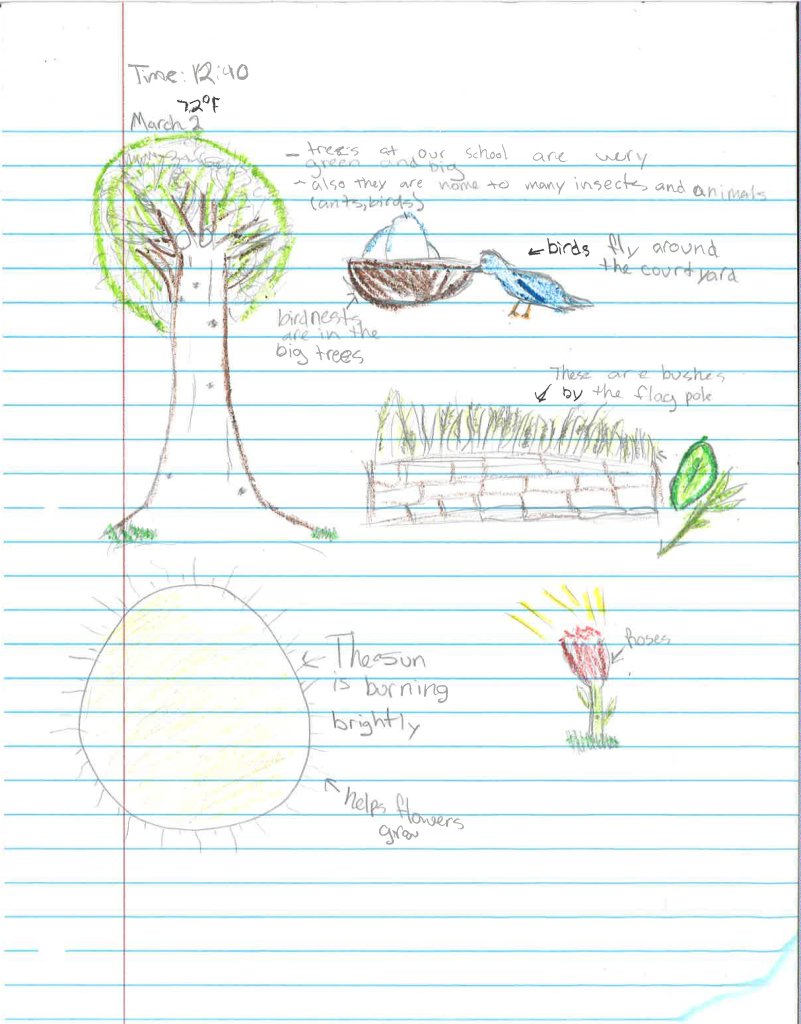

Nature journaling—sketching and annotating observations about natural phenomena—also builds crucial cognitive and processing skills like close observation, technical illustration, attention to detail, critical thinking, and the ability to organize and categorize information. “These connections reach across the disciplines to make learning more cohesive and increase overall brain development to improve learning in multiple areas of the curriculum,” explains Bollich.

When sketching and annotating in a journal, students process information in multiple ways, leading to deeper comprehension and more durable memories.

In a 2018 study, for example, researchers concluded that drawing is “an effective and reliable encoding strategy, far superior to writing”—largely because it forces students to actively process information across several modalities: semantic, kinesthetic, and visual. Ask a student to write down the parts of a flower—petal, pistil, and stem, for example—and the information will be quickly forgotten. Drawing a flower you’ve found and labeling parts and asking questions, however, encodes the material more deeply, resulting in richer, longer-lasting memories. In the study, the researchers found that students who visually represented science concepts like isotope and spore were nearly twice as likely to recall the information than students who simply wrote down the definitions.

To get students moving from the general to the more specific, high school English teacher Tanner Jones asks students to jot down 20 adjectives or phrases to describe the natural object they’re focused on. “At first, many offer broad observations like ‘The leaf is yellow,’” Tanner explains. “But as they spend more time and run out of obvious things to say, the observations become more nuanced and even beautiful: ‘The leaf is a heart with veins receding in size from the central stem.’” With time, students sharpen their observation and analytical skills, opening the door to complex inquiries such as, “Why do leaves turn yellow in the autumn?” and “What happens to this leaf after it snows?”

Connecting to Nature and Natural Rhythms

“Despite evidence for the benefits of the outdoors, the amount of time children are spending outdoors is in rapid decline,” researchers observe in a 2022 study, noting that children today spend less than half as much time outdoors as their parents did. Teenagers now spend an average of eight and a half hours each day watching television, playing video games, and using social media—activities that take a toll on their mental and emotional well-being, according to a Yale study published last year.

Schools, meanwhile, are slowly cutting off outdoor learning opportunities, as “insurance restrictions and the reduction of recess lengths coalesce to keep kids indoors,” Bollich writes.

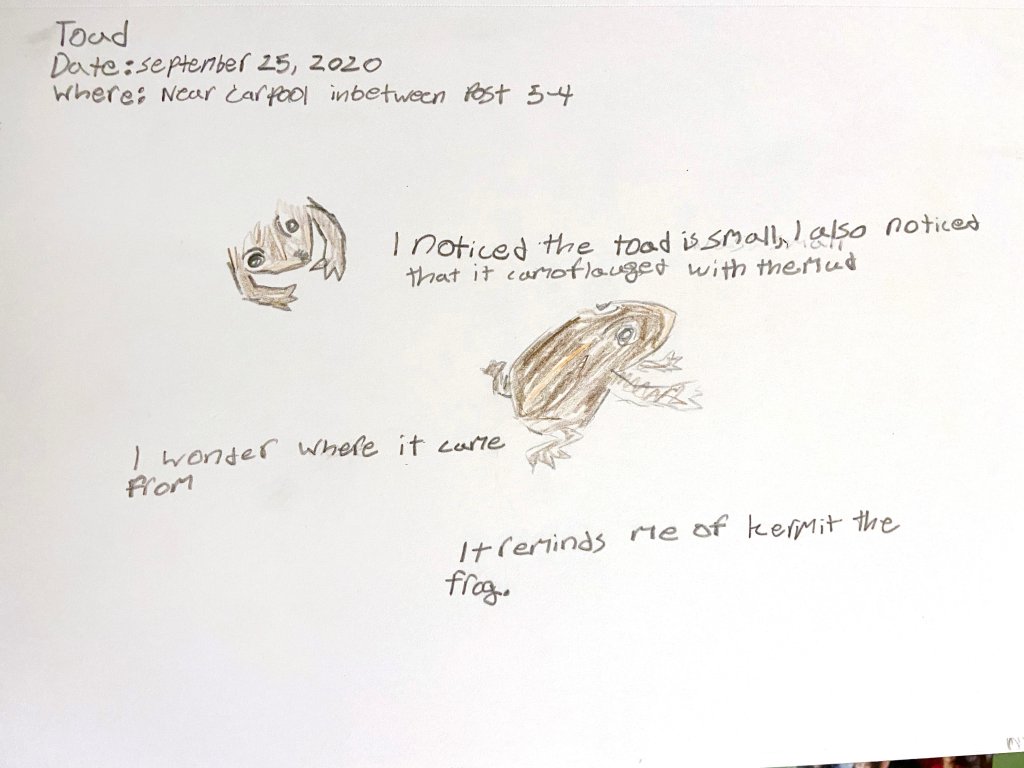

The upshot is that students are disconnected from nature and often feel apathetic about their local ecosystems. Nature journaling can be an effective antidote, helping young people “become familiar with the plants and animals that live near them, with the potential to increase their curiosity about these species,” suggests Bollich.

For elementary school teacher Sarah Keel, nature journals connect her students to the natural world. “The use of nature journals can be empowering for students as it helps increase their awareness of nature, gives them a sense of their place in their world, and encourages future conservation behaviors,” she writes. During a journaling activity, Keel asks students to find an outdoor “sit spot”—in a school garden, playground, home backyard, city park—and spend 20 to 30 minutes making observations. Prompts such as “What do you see, hear, or smell?” and “Did you observe any plant and animal interactions?” can help students get started.

A Breath of Fresh Air

“Students who learn outdoors perform better on standardized tests, are more engaged and motivated to learn, and are more focused on their work even when back indoors,” writes James Fester, a former social studies teacher and current teacher trainer. “Exposure to the natural world is associated with lower levels of stress, lower anxiety, and better overall social and emotional health.”

Researchers have long observed that learning in natural settings lends itself to a form of creative, student-directed play that is often absent in classrooms. A 2020 meta-analysis concluded that “nature play had positive impacts on developmental outcomes for children, particularly in the cognitive domains of imagination, creativity, and dramatic play.” Studying a neatly rendered diagram of a tree or bird in a textbook tends to produce a detached appreciation that’s at odds with how Darwin approached scientific inquiry. Not only are students more likely to be “smiling and laughing” in natural spaces, but they’re also more imaginative and more willing to collaborate with their peers, the researchers found.

How can you get started? Your first foray into nature journaling doesn’t have to be a major expedition, and you don’t have to be a wildlife expert to lead a successful trip, says fifth-grade science teacher Pete Barnes.

Nearby trees, rocks, and bushes are teeming with life, and kids will be quick to notice. “Students marvel at the smallest of natural encounters—spotting a frog, running alongside a butterfly, or discovering a beetle beneath a log,” Barnes writes. Give them a chance, and they’ll take to it quickly, at virtually all grade levels.