Writing Aloud: Staging Plays for Active Learning

Theater projects make middle school students invest in their writing.

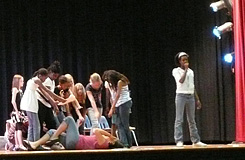

A dozen middle school students wiggle their limbs and recite lines at increasingly louder decibels to warm up their bodies and voices. They are at a rehearsal for the play they wrote about three channel-surfing friends who get sucked into a television set and witness racial discrimination.

For the Stuart-Hobson Middle School class, the play was the final piece of the yearlong Student Playwrights Project, run by the Arena Stage theater company for secondary school classes. Students write individual ten-minute plays and group plays, and they take part in a playwriting competition for the Washington, DC, area.

The aim of the Arena Stage program, like that of similar theater-education programs across the country, is to offer the benefits of arts education at a time when schools are increasingly putting the subject on the back burner. Playwriting teaches kids how to construct a plot, write dialogue, and tell a story through action. But the benefits go far beyond that. Students also learn how to conduct research, perform in front of an audience, collaborate with their peers, and express themselves, says Adrienne Nelson, the Arena Stage teaching artist who worked with the class of thirty-two Stuart-Hobson students this year.

Writing and performing their own work "teaches them a hundred times more than what they'd learn performing a little historical piece," Nelson says. "They're more invested when they've written it. And they learn key skills." Nelson creates her own lesson plans, which she models after plans provided by the Arena Stage. They include teaching objectives, warm-up activities, and writing prompts to get students started. (Download a sample lesson plan.)

Unfortunately, playwriting isn't a priority in many school curriculums, says Elyse Eidman-Aadahl, director of national programs and site development with the National Writing Project. "People really don't understand there are benefits," Eidman-Aadahl states. "They don't see how it builds thinking and cooperation skills." It's also a time issue. She notes that teachers are busy preparing students for the writing found on state standardized tests, making it hard to squeeze playwriting in.

However, teachers who want to give their students the benefits of playwriting programs often need to look no further than their local theater. Cecelia Kouma, managing director of San Diego's Playwrights Project, says that to help schools fill the gap, more theater companies are focusing their education outreach on playwriting rather than just on theater appreciation. Theaters across the country have educational-outreach programs in playwriting, and though the more intensive residencies aren't always free, free options abound, from downloadable lesson plans to one-day workshops to full-year programs. There also are a number of resources on the Web.

Finding the Message

One of the striking things about the plays that students write is their subject matter. Jim DeVivo, education director with the Playwrights Theatre, in Madison, New Jersey, says he sees some pretty personal plays through his theater's education program. "They're very frank, and a lot of times they're very creative," he adds. For example, one student wrote a play about bullying, in which aliens from another planet observe life on Earth and intervene to help the characters through a conflict.

The Stuart-Hobson students -- who participate in the program as an extracurricular activity at their school -- wrote their group play, Are We Trapped Here?, about the discrimination faced by African American contralto Marion Anderson when she performed in Washington, DC. A student named Kelsea wrote her individual play about global warming; the story is told through newscasts about rising temperatures. Winning plays from other schools in the ten-minute-play competition this year dealt with the Underground Railroad, a homicidal teenager tormented by personal demons, and estranged siblings fighting at their gay father's funeral.

"Most of the time, when you write a play, it ends up having a message, even if you don't predict it at first," says Meridian, an eighth grader at Stuart-Hobson whose play about female pirates garnered an honorable mention in the 2008 competition. "I was saying that women can do anything."

Meridian's play, like those written by many of the students, also required her to conduct historical research because it was about two real-life female pirates who ended up on the same ship. The research lends authenticity to the play, but Meridian says another type of analysis really helped polish up the piece -- listening to a classmate read a draft. "You hear certain things that just don't click and you have to figure out what's wrong," Meridian says. "When you're in your own little corner writing, you might think it's the best thing in the entire universe, and then somebody else reads it, and it's like, 'What?'"

Feedback Is Its Own Lesson

That process of giving and receiving constructive feedback instills valuable communication and critical-thinking skills, and it's something students don't often get as part of the regular curriculum, notes the Arena Stage's Adrienne Nelson. For the group play, the Stuart-Hobson students had to defend their own ideas and offer opinions on those of their classmates, teaching them how to work together and talk things through. Nelson says she emphasizes something with her students: "It doesn't matter how talented or smart you are," she tells them. "If you can't communicate your ideas respectfully, you're going to have a really hard time in your life, in your studies, in your world."

For the individual plays, too, communication is a key lesson. Whereas most school writing is done for just the teacher, that's not the case with a play. "They're also writing for an unknown number of people who are going to observe it or are going to access the story," says the Playwrights Theatre's Jim DeVivo. When the student writers go through feedback sessions, whether it's with a group or one-on-one, they learn how to rewrite their plays to get their message to a wider audience.

There's also a power in performance. "When they know that an actor is going to perform their words, they focus more on them," says the Playwrights Project's Cecelia Kouma. Often, students think editing their work simply means correcting spelling and punctuation errors. After they hear an actor read their scripts, however, the students approach the editing process more seriously, making changes that strengthen major aspects of the work. "It's deeper, more profound kinds of revision that they become focused on," says Kouma.

Eighth grader Meridian describes her experience with the playwriting program as wonderful. In 2007, she placed third in the ten-minute-play competition -- and, with the other top ten winners, got a staged reading of her play, a twist on Romeo and Juliet. Watching her play performed was "one of the greatest things in the world," she proclaims. "It gives you the feeling of accomplishing something really big, like when you get an A on a final or you hit a home run."

Alexandra R. Moses is a freelance writer in the Washington, DC, area who specializes in education.

Set the Stage: Resources for Teaching Playwriting

The following information can help you get started developing a playwriting program.

Where to Find Playwriting Lessons

A number of Web sites offer free materials for educators to help them incorporate playwriting into their curriculum. Here's a sampling:

- Centerstage, in Baltimore, has a free, downloadable twenty-six-page handbook titled Teaching Playwriting in Schools, which offers ideas on how to use playwriting across the curriculum and how to address common problems found in student plays. It also details some classroom activities to aid the process. One of the activities is a playwriting questionnaire to help students develop their plots.

- The Herberger College of the Arts, at Arizona State University, in Tempe, maintains a Web guide, ArtsWork, which includes a section on incorporating drama into general subjects for grades 3-8. It offers a variety of short lessons, such as scenario writing, dramatic writing, and improvisation. And for each lesson, there are activities, assessment questions, and estimates about how long the lesson takes to complete.

- The Young Playwrights' Theater, in Washington, DC, offers resources for teachers and students, including a downloadable lesson plan on creating characters and conflict, and a worksheet detailing the five stages of playwriting. You can also download an example of proper script format.

Integration Tips

Teachers don't have to go through a formal theater program to use playwriting across the curriculum. Jim DeVivo, with the Playwrights Theatre, in Madison, New Jersey, says an English teacher can tie playwriting to a current reading assignment by asking students to focus on a character and write an original monologue for that character. If the class is reading Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird, for example, students can create a new scene between Jem and Scout and build from there. Students also can give one another feedback through roundtable discussions or script swaps. For constructive feedback, DeVivo says students should start suggestions with the phrase "You may want to consider . . . ."

History and social studies teachers also can use playwriting. Cecelia Kouma, with the Playwrights Project, in San Diego, says students can set plays in the specific time period they're studying, such the California gold rush or the time of the pilgrims, or they can include a character from mythology if their topic is ancient Greece. To keep the plays personal, she suggests writing prompts that help students make connections to their own lives. For example, for a play set during the gold rush, teachers can ask students to consider what it would be like to move across the country, and, if they could bring just a few possessions, which they would choose.

Playwriting Programs

Here are some of the theaters and theater-outreach groups across the country that offer workshops, seminars, and residencies on playwriting for teachers and K-12 students:

- Arena Stage, Washington, DC

- Vermont Stage Company, Burlington, Vermont

- Centerstage, Baltimore

- Playwrights Project, San Diego

- Young Playwrights, New York City

- Philadelphia Young Playwrights

- Playwrights Theatre's New Jersey Writers Project