The Five Features of Science Inquiry: How do you know?

STEM blogger Eric Brunsell outlines the five features of science inquiry

Teaching science through science inquiry is the cornerstone of good teaching.

Teaching science through science inquiry is the cornerstone of good teaching. Unfortunately, an inquiry-approach to teaching science is not the norm in schools as "many teachers are still striving to build a shared understanding of what science as inquiry means, and at a more practical level, what it looks like in the classroom (Keeley, 2008)." A good starting point for understanding what science inquiry "means" is to focus on the definition provided by the National Research Council.

The 5 features of science inquiry (emphasis is mine)

- Learner Engages in Scientifically Oriented Questions

- Learner Gives Priority to Evidence in Responding to Questions

- Learner Formulates Explanations from Evidence

- Learner Connects Explanations to Scientific Knowledge

- Learner Communicates and Justifies Explanations

Although each component is important, notice how many times the words "evidence" and "explanation" are used. Helping students use evidence to create explanations for natural phenomena is central to science inquiry. In their article, Argument Driven Inquiry, Sampson and Groom write (emphasis mine):

"In America's Lab Report: Investigations in High School Science (200) [http://www.nap.edu/catalog.php?record_id=11311], the National Research Council (NRC) makes several suggestions for how laboratory activities can be changed to improve students' skills and understanding of science: First, laboratory activities need to be more inquiry-based so students can develop practical skills and an understanding of the ambiguity and complexity associated with empirical work in science. Second, students need opportunities to read, write, and engage in critical discussions as they work. Finally, it is important to encourage students to construct or critique arguments (i.e., an explanation supported by one or more reasons) and to embed diagnostic, formative, or educative assessment into the instruction sequence."

There are many ways that you can reinforce the creation and critiquing of arguments in your classroom. "How do you know?" should be one of the most frequently asked questions in your classroom. You should expect that student answers (verbal or written) should include evidence. Additionally, you should look for opportunities for students to critique the use of evidence in science news, reports and other media.

Some practical classroom examples of giving priority to evidence

Mallory Fredrickson, a middle school science teacher at New Richmond middle school in Wisconsin, introduces her students to the concept of making evidence-based explanations by using a story about a mysterious death. Students find evidence in the story to create a theory about how Mr. Brown died. Mallory explains, "They realized how it's [related to] science and how I expect to see them coming up with explanations this way all year."

Chad Janowski and his colleagues at Shawano High School (WI) developed common laboratory expectations for their students that expect students to give priority to evidence by explicitly asking them to provide the evidence that supports their conclusions and to also provide a rationale that connects the evidence to the claim. Chad notes that using evidence isn't automatic, "I gave this [the new laboratory report expectations] out to my students on Friday and watched them struggle to work through it. I cannot wait to see the progress they make as they use it throughout the year."

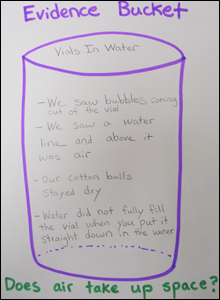

Brian, a high school teacher working with researchers at the University of Washington, used "evidence buckets" to help students organize data from laboratory experience. Students could easily see connections between different pieces of evidence as they make meaning of class activities. Watch a video at Tools4TeachingScience.org to see evidence buckets in action.

Lisa Sullivan, a teacher at McKinley Elementary in Kenosha, Wisconsin, modified evidence buckets to use with her 2nd grade students. She focused her students on the question, "Does air take up space?" as they explored a variety of activities. She then helped them organize their observations using evidence buckets. Lisa commented, "I realized that we couldn't make an evidence bucket until they understood what evidence was. One child said that he knew that they used evidence in court. This was a good example and I told them that evidence was what people observed. It could be used as proof of something or used to help explain an idea." She continued, "After we filled in our evidence bucket I called on a few students to raise their hands and tell me what they would say to someone who asked them: Does air take up space? I told them that the more evidence they used in their answer the more likely it was that the person would believe them. They did a great job of connecting their arguments to the evidence bucket."

--- Don't forget ---

Invite a scientist, engineer or other STEM professional into your classroom and enter the #scichat challenge!