Beyond “The Wire”: A Baltimore School Changes the Channel

While the celebrated HBO series turns its lens on the city’s failing urban schools, one high school there strives for success.

To the world outside of inner city schools, teachers are often ambassadors, and so they frequently talk only about their students' struggles and the bureaucracies that entangle schools among themselves. "I'm not going to tell stories about a lot of the tragedies or violence or mismanagement," says former West Baltimore teacher Carla Finklestein, "because I don't want to be responsible for furthering anybody's stereotypes."

But Finklestein and others in Baltimore public schools relish having the critically acclaimed HBO television series The Wire's gaze fixed on their world. Rather than simply exalting a white teacher, or alternately demonizing and romanticizing struggling students, the program (whose fourth season comes out on DVD in December 2007) requires its viewers to engage with and learn about urban schools and the lives of people in them.

The fourth-season's story arc, set in a neighborhood middle school, continues The Wire's unflinching look at institutions and urban poverty, but it also explores how schools might be made to work for more kids, even the most seemingly unreachable. Located in the same West Baltimore neighborhood as the fictional school in The Wire, one small learning environment, Baltimore Talent Development High School, is doing this imagining in real life.

Antonio Brown, a senior at Baltimore Talent, appreciates the show's focus on "corner kids," those with the least family support and most street influence. For Brown, The Wire affirms the significance of his academic achievement in a system in which the majority of students drop out. Notes Brown, "It shows the struggle and the trouble that young people in the city go through, for real, and what we have to overcome, what we have to do to get out of our situations."

A Real Baltimore School

Part of Brown's success, surely, is that he attends a school that doesn't operate like the one depicted on The Wire. The Baltimore City Public Schools has started systemic reform efforts, incorporating middle school students into K–8 schools and dividing large neighborhood high schools into multiplexes, with small academies sharing larger campuses.

Baltimore Talent, one such school, is located across from a funeral home in a West Baltimore neighborhood where blocks and blocks of structurally beautiful row houses are boarded up and vacant. Ninety percent of the students qualify for free-lunch or reduced-lunch programs. "When I look out at the cafeteria, I say, 'If it weren't for this school, there'd be thirty-five to forty kids who would not have made it to be seniors. I know that for a fact," says Principal Jeffrey Robinson. "We have minimum dropouts compared with other schools in the city. The dropouts are in the single digits." According to John Snoddy, a counselor at the school, of the 570 students who have ever enrolled at Baltimore Talent, only eleven have dropped out.

The Talent Development model came out of nearby Johns Hopkins University's Center for Social Organization of Schools, which has Talent Development sites in thirty-eight states. "The premise of the model is double dosing," says Robinson. Citing academic failure as the most significant reason for dropouts, he explains that Baltimore Talent students double up on classes in key content areas, taking the equivalent of two English courses and math classes in their ninth-grade year, with skill-building courses in the first semester. Because most Baltimore Talent students come in below grade level, this schedule "better prepares them to succeed and pass and move on to tenth grade," explains Robinson.

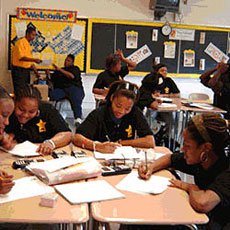

The academic design assists in boosting students' achievement and esteem, but the school's small size also allows kids to build unusually tight relationships with Baltimore Talent's adults; teachers are on teams with the same sixty to seventy-five students all day.

Big Man on Campus

This is Robinson's fourth year as principal of Baltimore Talent. Walking to the school's cafeteria, he talks playfully but seriously with kids, all of whom he knows by name. Robinson also stops a fight between middle school students from the adjoining campus, but Baltimore Talent seems to exist in a different, calmer plane. In the cafeteria, seniors in blue shirts occupy one side; juniors in yellow shirts eat on the other. And though they're pretty loud and silly, these students follow the posted rules and listen when Robinson gets on the microphone to make daily announcements.

Start the Day with a Smile: Principal Jeffrey Robinson is optimistic about his students.

Credit: Sutikare Oluwagbenga/BTDHSThe school integrates character building into its curriculum, has university and community members meet with students to review report cards and plan improvements, and celebrates students' achievements through ceremonies and postings and prizes. These things are "virtually impossible to do in a big school," Robinson points out.

But he's careful not to overstate Baltimore Talent's success. "It's frustrating at times. And we do get burned by the corner kids we're trying to help," he says. "We put ourselves out there, talk to them, buy them uniforms, and they can cuss us out and not show up. That comes with the territory. You try not to take it personally. But you do save some as well. You don't win every battle, but you do win some."

The Wire is one of Robinson's favorite shows, and he recognizes the type of school in which the fourth season is set. "It was a very fair representation of what it was like being in some schools," he says, "and it just made me appreciate what we're doing here." Being real about kids' lives is essential to the success of both the show and Baltimore Talent.

"We always tell kids, 'There are two rules,'" Robinson says. "'You got your street law, and I'm not going to tell you how to behave once you're in the street. But there's school law as well. I can't tell them to walk away or do what's right in the street, because that's a different code.' I tell them, 'When you're in school, we have our rules, and if you want to stay here, you've got to abide by our rules.'" He says staff members continually counsel students that there are ways out of poverty, but he adds, "The only foolproof way I know is through education."