Disabled Bodies, Able Minds: Giving Voice, Movement, and Independence to the Physically Challenged

Assistive technology makes it possible for students without full mobility to participate in class and school activities.

"It took us three years," says Adrian's teacher, George Rehmet, of the amount of time they spent trying to locate a place on Adrian's body that would allow him to communicate with using a computer. This particular computer has pictures tailored especially for Adrian: photographs or pictures of friends and family, including his baby sister, Alexis, and pictures or words depicting situations or events he would like to write about, such as the weather, trips with family, and meal preferences.

Adrian, who is taking part in a districtwide program known as TACLE (Technology and Augmentative Communication for Learning Enhancement), wears a headband that can sense the movement on his eyebrows. That motion triggers the computer cursor to move to a row or column on the monitor that illustrates what he's trying to express. The computer then utters the words Adrian has chosen.

Eight-year-old Niara, who has cerebral palsy, sits next to Adrian. Like her classmate, she uses a wheelchair and speech-generation technology, using her cheek to communicate using the computer. When Rehmet asks Niara what she needs, for example, she makes some movements with her cheek, and immediately from the computer come the spoken words: "A hug." Rehmet gives her one.

Students in this special-education class at Redwood Heights Elementary School, in Oakland, California, come to school with a range of disabilities, and the goal of the district and teachers is to design whatever plan is necessary to allow the students to achieve their potential. Some students use the speech-generation devices as a backup to signing or to conversation that is unintelligible to the uninitiated listener. For others, computer speech is the only way they can communicate.

New Tools, New Opportunities

All over the country, what is known as assistive technology is opening the way for disabled students to do what their counterparts of years gone by could not even have imagined. "We all know how technology has improved in the last few years," says Sheryl Burgstahler, director of DO-IT (Disabilities, Opportunities, Internetworking, and Technology), an advocacy program for disabled students at the University of Washington. "What most people don't realize is that assistive technology has been progressing at the same rate."

Susanna Sweeney-Martini, an outgoing, articulate University of Washington sophomore who wants to be a television news anchor, says she couldn't function like she does today without assistive technology. "Without a computer, I couldn't do my homework," she says. "Without my [wheel]chair, I couldn't get around. Without my cell phone, I couldn't call for help."

No Limits

DO-IT, the federal Americans with Disabilities Act, and other widespread efforts and laws seem to have created a greater determination among students and parents to make sure disabled people are included in all activities. Kristy Bratcher, the mother of Lukas, a high school sophomore in Spokane, Washington, who has extremely limited use of his arms and legs as a result of a birth defect, didn't hesitate to encourage him when Lukas expressed an interest in playing a musical instrument.

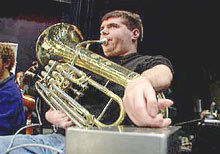

"I always kept trying to find things that Lukas could do with peers other than an athletic event," says Bratcher. "Everything is sport, sports, sports." So when he brought home a note seeking permission to play a band instrument, she signed it and said, "Lukas, just go and see what's going to work." The Mead High School student chose a euphonium, a tuba-like horn.

Lukas at first just blew into the euphonium without using the finger valves, but his system meant he could play only one note. Although he patiently waited until that note showed up in a musical score and seemed happy to do just that, his patience and upbeat attitude paid off. A school employee sought out a music-store owner named Robin Amend, who is also a musical-instrument inventor and repairman. Amend, whose grandfather had played a musical instrument despite having only one arm, designed a euphonium with a joystick that electronically instructs the valves of the euphonium to move. Later, an engineer worked with Amend to refine the joystick technology.

Lukas may have some mechanical help with his instrument, but music teacher Terry Lack says his personality is what has turned his desire to play an instrument and be part of the band into reality. "He always has a smile on his face and has a really positive attitude," says Lack. "[That's] the real key."

Lukas' mom says her son's participation in the school band has given him a chance to stretch himself and see what he is capable of accomplishing. "I can't predecide what's going to work for him or not," she says. "So many people say, 'You can't. You can't.' Why do we have to talk that way? Let's just see what it is and what he has an interest in, and we'll figure it out."

No More Excuses

DO-IT's Burgstahler has little patience for school officials who don't think they have a responsibility to include those with disabilities in every school activity possible or who believe a full-time aide can substitute for technology that gives the students more independence. "If they have access to their own computers, they can take their own notes, they can take their own tests, they can write their own papers, they can use the Internet and do their own research," she says.

And as to concerns about the high cost of assistive technology, Burgstahler points to the benefits, and she wonders how schools can justify not investing in tools for disabled students.

"Students can now use their brainpower instead of their physical capabilities to go to college and then on to careers so they can have the life all of us want to have," she says. "They can have the American dream."