A Public School Makes the Case for ‘Montessori for All’

A Title I public school in rural South Carolina is proving that Montessori education can work well anywhere.

The five miles from Interstate 95 into Latta, South Carolina, amble past fireworks shops and stretches of farmland bordered by matchstick pines and interspersed with the occasional home. Railroad tracks and a lone post office mark the center of town, home to 1,300 people and one elementary school, one middle school, and one high school that serve students in a county nearly 100 miles wide.

In many ways, Latta is no different from other communities scattered throughout the rural South: Jobs are limited, businesses are local, and residents know one another. But the opening of a Title I public Montessori school has put this small town at the forefront of a movement that is upending the status quo around access to progressive education.

More than a century old, Montessori education takes a holistic, child-centered approach to teaching and learning that researchers say is effective, but for decades these schools have largely been the domain of affluent, white families. Nationally, estimates suggest that between 80 to 90 percent of U.S. Montessori schools are private, and most are concentrated in urban or suburban enclaves—not communities like Latta, where the median income is $24,000.

“My expectations have always been really high regardless of where you come from,” says Dollie Morrell, principal of Latta Elementary, where more than 70 percent of the 661 students receive free or reduced price lunch and nearly half are students of color. “One of the biggest misconceptions about Montessori education is that it is just for privileged children in the private sector, but as a large public school, we’re showing that Montessori works for every child.”

While Latta Elementary is one of the largest public Montessori schools in South Carolina—the state with the highest number of public Montessori schools in the nation—it’s not a complete outlier. From 2000 to 2015, more than 300 public Montessori schools have opened across the U.S., often in low-income and racially diverse communities, including Puerto Rico and cities like Boston, Detroit, and San Antonio.

Student gains have also increasingly been supported by research, tracked to Montessori’s dual emphasis on academic and social and emotional learning.

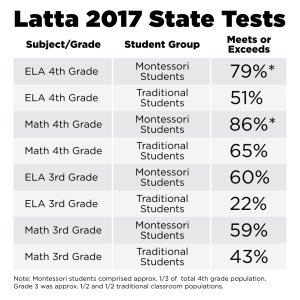

A study released last year by Furman University revealed that public Montessori students in South Carolina outperformed their non-Montessori counterparts on standardized tests and a variety of social and emotional metrics. Meanwhile, a three-year study of preschool students in Hartford, Connecticut, found that public Montessori schools helped close the achievement gap between higher- and lower-income students, and that students in Montessori schools performed better overall academically.

A Time-Tested Approach

At Latta Elementary, soft music playing on boomboxes wafts through the hallways, but otherwise, it’s surprisingly quiet. Inside classrooms, children as young as 4 grab a quick breakfast before self-selecting colorful, handheld lessons from small shelves that line the walls. They join other children of different ages who are scattered all over the floor, sitting or lying on their bellies, intently focused on various activities they’ve spread out on kid-sized beige rugs. Their teacher wanders throughout the room, pausing to squat down and help as needed.

Latta’s classrooms didn’t always look this way. Desks were placed in orderly rows, teachers delivered whole-class lessons, and students received report cards with letter grades.

“We were basically a pretty traditional school district in teaching methods and instruction, but what I felt like was missing was, is this what our students need? Are we making learning interesting? Are we making learning relevant?” reflects Superintendent John Kirby, who has served in the position for nearly 30 years. “We were not looking at the long haul. The school system is the best chance our students have to compete in the world.”

Latta Elementary School

On a mission to make learning more forward-looking and engaging for every child, Kirby tasked district administrators with developing new schoolwide approaches to prepare their students to be successful—in school and beyond their small, rural community. In response, the high school established an International Baccalaureate (IB) program, the middle school now has a STEM focus, and the elementary school became a Montessori school.

“We had naysayers that said, ‘You’re too small, you’re too poor, your kids aren’t smart enough.’ It was a big task for us,” says Kirby, who, along with Morrell, was particularly attracted to Montessori’s whole-child approach to education, which has roots that reach back to the turn of the 20th century.

In 1907, Italian physician Maria Montessori opened Casa dei Bambini (“Children’s House”) to keep underprivileged kids in school and off the streets of Rome. A keen observer and researcher of child development, Montessori developed tactile learning materials and child-centered teaching practices based on how she believed kids learn best—with movement, independence, and choice. Her unique pedagogies and classroom structure gained popularity and were soon adopted in schools all over the world, and they are still used today.

To an outsider, a Montessori classroom may seem chaotic, but every component—from the layout to the school schedule—is designed with specific purpose, emphasizes Angeline Lillard, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia who has conducted research on Montessori schools for the last 15 years.

These practices are also increasingly supported by research, says Lillard, who is the author of the book Montessori: The Science Behind the Genius. The three hours of uninterrupted work time given to students each morning help children develop executive functioning skills, like focusing on a task and managing time efficiently, which have proven to be decisive in giving kids a leg up in school and life. Additionally, the flexibility to move around the classroom has been shown to stimulate learning and improve academic performance, while choice in lessons provides a sense of autonomy that can boost motivation and engagement.

‘One of the Most Difficult Things’

Merits aside, the considerable differences between traditional public education and the Montessori approach made Latta Elementary’s transition “one of the most difficult things the teachers have ever done,” says Morrell. The process took five years, as the school shifted classrooms and staff in batches. For teachers, this meant balancing a full-time job with more than two years of nightly and summer trainings in nearby Florence.

Extensive training—comparable to graduate school coursework—is necessary as the Montessori curriculum challenges educators to rethink fundamental classroom dynamics, right down to the roles of teacher and student. Instead of delivering whole-class lessons, teachers prepare individualized work plans for every child every week, and circulate around the room during class time to help and observe students individually.

“As a traditional teacher, I felt like I was telling them what they needed to know; now I feel like I’m showing them the way to learn,” says teacher Amanda Smith, who, along with her colleagues, had to switch from teaching individual grades to teaching multiage classrooms—a cornerstone of Montessori schools that encourages peer-to-peer learning.

Many of the core subjects, such as math, also required a new approach to instruction—employing tactile materials to build students’ foundational understanding before moving to high-level, abstract concepts. A soft-skills component of the curriculum teaches students to take responsibility for their indoor and outdoor environment through activities like washing dishes, caring for a classroom pet and a coop of chickens, and maintaining a garden.

“Montessori is just a different way of learning. We still have to cover all of the same standards as any other public school, I think we just go further,” says Smith, who adds that the hardest part has been preparing students for state testing in a model that does not encourage testing—or grades or homework, for that matter.

The challenge of standards and testing is not unique to Latta and has been cited as one reason—along with the high costs of materials and teacher training—that there are relatively few public Montessori schools.

But the results show that Montessori students are testing well. Before the entire school transitioned to Montessori, Latta compared the state test scores of non-Montessori to Montessori students and found that Montessori students significantly outperformed their peers on math and English language arts (ELA) tests, with 86 percent of Montessori students meeting or exceeding state standards in math in 2017 and 79 percent doing so in ELA.

A Family Matter

Because of the challenges, some schools implement only a partial Montessori curriculum, which can result in skewed public perceptions about what Montessori education is and what it isn’t, according to Mira Debs, a researcher who is the executive director of the Education Studies Program at Yale University and the author of Diverse Families, Desirable Schools, a book on public Montessori schools.

Debs emphasizes the importance of families to the expansion of Montessori, and has found that messaging and framing can have considerable impacts on which families are attracted to Montessori schools.

In a study of public Montessori magnet schools in Hartford, Connecticut, Debs found that white families at the schools were generally more comfortable with the approach than black and Latino families, who expressed more concerns about long-term academic success for their children. “One of the key problems I see is a tendency to downplay the academics benefits of Montessori in emphasizing the whole-child benefits,” says Debs, who notes that families of color she interviewed tended to have fewer options for school choice. “That can be a turn-off to families who are really seeking clear reassurance of the academic benefits of a particular school.”

In Latta, school leaders realized quickly that parent buy-in would be critical. The district had to convince them it wasn’t “witchcraft or just for artsy kids,” said Superintendent Kirby half-jokingly, stressing the contrast between the old and new approaches. To build acceptance, the school originally offered Montessori as in opt-in program for individual classes, and required parents to observe the classrooms and attend information sessions to make the system less mysterious.

“I had heard of Montessori, but had no earthly idea what it really was. It wasn’t until I got into my first classroom observation that I understood how it worked,” says Rachel Caulder, a Latta Elementary parent and a high school teacher. Once parents started to see the benefits, they chatted at sports events and school drop-off, creating a domino effect of demand for Montessori that helped transition the entire school.

While Caulder’s two children are very different, both have become more independent and creative learners in Montessori. In particular, they’ve developed a greater sense of responsibility—for themselves, for their schooling, and for their environment.

“I’ve been amazed at their understanding of their place in the world. And they always start with that, ‘I am here.’ They start with Latta, but then they understand how that grows and how that broadens,” she said.