Helping Troubled Students, One Relationship at a Time

Many students don’t trust anyone at school. To address that, we asked teachers to forge one-on-one bonds with these kids.

When Jimmy, a 6th grader with significant social and emotional disabilities, was sent out of English class every day one week, he devised a plan. On Friday, he smuggled a pair of handcuffs into school, and upon arriving at English class, instead of grabbing his “do now” and sitting down, he ran straight to the teacher’s desk and handcuffed himself to it.

The teacher, a kind and in many ways excellent instructor, was shocked. The teacher and I unlocked Jimmy soon enough, but later, when we had a quiet moment to reflect, I said, “You teach English. Can you see the symbolism here?” Jimmy desperately wanted to stay in class but did not know how. And to compound this tiny tragedy, it seemed obvious he had no one to ask.

As the dean of culture at a new school in Springfield, Massachusetts, I sought to gather data before discussing the incident with the staff. I administered a relationship survey that asked only a few questions:

- How many teachers do you trust?

- How many staff/teachers do you feel you can go to for help?

- And how many staff/teachers do you feel you have a strong relationship with?

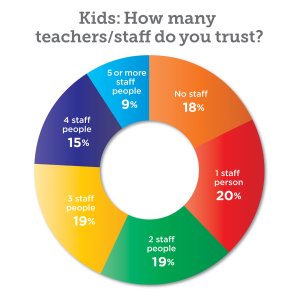

While the school had a student population of over 400, I received only 180 surveys back. Our results are in the chart at left.

This was heartbreaking. Nearly 20% of our students trusted no one. We were asking students to learn traditional subjects -- math, science, etc. -- in an atmosphere where they felt that no one had their best interests at heart. They came to school expecting to struggle, and then they made it true.

After presenting my findings to the staff, I explained what we were going to do. Our primary goal was to systematically move the needle until every student had at least one person they looked forward to seeing in the morning, and then to use that momentum to build the relations between staff and students for every single student. We divided teachers by grade level and asked each teacher to pick one student. For the first few weeks we asked them to limit their choice to students who had said on their surveys that they trusted no one. After they chose, we gave the teachers a worksheet that included these questions: What is the student’s living situation? Favorite games? Favorite sport? Taste in music? What is the student good at? What is the best part of their day? What is the worst?

In conversation with Jimmy, I asked him what he wished teachers knew about him.

His answer broke my heart. He said, “I wish teachers knew I was good at some things.”

Building Trust

Our questions were not picked at random. We avoided traditional questions such as “What do you see in your future?” Poor students regard this line of questioning as a trap because the answer will always be that their effort is not sufficient to reach their goals. Instead, we wanted to know who each student was right then. I encouraged teachers to answer each question themselves after listening to the student, and made sure to add space on the worksheet for their responses, so they could share the answers with the student. After all, relationships are not one way. Just as we needed staff to see students as whole people, we needed students to see each staff member as a whole person.

Each teacher was responsible for finding time for a long conversation with the student. I suggested a private lunch, but recognizing that some of our staff insisted on their contractually allocated break, we also allowed the student to be pulled from phys ed, art, or technology classes. Within one week, teachers were to upload their results to a shared document and then pick another student.

Here are a few tips for building relationships with students:

- Keep the conversation in the present. Your relationship is happening now. This is where the conversation needs to be.

- Listen carefully. Repeat enough so the student knows you listened.

- Reveal yourself. Some teachers fear that if students know who they really are the students might use that knowledge as ammo. Ammo for what? How can they hurt you for being yourself?

- Offer food. Not a piece of candy, not a reward or a bribe. Open a bag of chips and eat one and then offer some to the student. This is primal, this is true caring and thoughtfulness. Sharing food recognizes two individuals. It quickly begins the process of building a positive relationship.

The results were instantaneous and stunningly positive. In the private conversations, teachers learned things that caused them to adjust their style, resulting in less student misbehavior and more time in class. When kids skipped a class, it used to take a significant amount of time to find them, but in several cases after we began this program we just went to the classroom of the person they trusted and found the student there. Approaching relationship building as a school-wide value shifted the culture significantly to the positive.