Encouraging Students to Own Their Work

Bringing choice into your classroom helps you give your students chances to create work that matters to them.

Learning changes dramatically when students have opportunities to produce work that matters to them. We know this from our own lives but don’t always do a good job of honoring it in schools. It’s easy for me to recall times when I dragged my feet completing a task, or rushed through a requirement that was imposed on me. And I have memories of skipping meals or staying up too late to work on projects that felt meaningful.

When I examine and reflect on my students’ work, I discover insights and truths about their learning experiences. Some students find ways to create work that represents a deep connection to and exploration of content. Others don’t feel engaged or invested in what they’re doing—and their final products are rushed and superficial.

My work, and I believe the work of schools, is to create more opportunities for students to connect with content and produce work that they feel they own. Rather than submit something that’s an exercise in going through the motions, students should have opportunities to create work that allows them to investigate issues that feel meaningful to them. It’s not that project criteria should be forgotten, but rather that we should design learning that provides students with opportunities and possibilities.

Classroom Examples

Earlier this year, my 12th-grade English classes investigated the topic Media and the Mental Environment. Students had to keep a Media/Mental Environment Diary; they read, watched, and responded to different sources in order to become informed media consumers; and they created Media Mini-Portfolios.

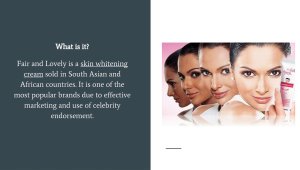

Rifah created Unfair, Not Lovely, a presentation on the marketing of skin-whitening creams sold in many South Asian and African countries. She reflected on her work: “I am most connected to school work when I can relate to it or see a deeper meaning behind it. . . . As a South Asian American, I find it really hard to bring both sides of my culture together in my life, let alone a school project. Through this project, I found myself able to merge these two clashing cultures together beautifully. . . . I hope to continue to do work like this where I can use what I learn in the classroom and apply it to relevant issues in my life.”

In a different class, Jordan wrote an Advanced Essay as part of our unit Investigating Literacy. (This is the project description.) In his essay, “The Young and the Illiterate,” he was able to develop a connection to the work by examining his early experiences of literacy and racial consciousness: “I run up the steps with excitement as I do not want to be late to class and miss the opportunity to see my friends. The teacher of my Kindergarten class, Mrs. D, greets me at the door. ‘Welcome Jordan, are you ready to learn today?’ she asks. I respond with a bright smile exposing her to the missing teeth in my mouth. Mrs. D was an older, large, white woman. I was one of only three black children in her class. She often made all of us sit together, so it would be easier to teach us collectively, I now assume.”

Tajnia created meaning through an assignment by sharing her fears with classmates. After we read the poem “Theme for English B” by Langston Hughes, students wrote their own poems entitled “Theme for English 3.” They shared what they wrote out loud with the rest of the class. Tajnia shared this: “This is the reason I am afraid. I don't want to experience my hijab being pulled off from my head because I want to dress modestly. I don’t want to be on a plane reading the Quran and kicked off because I am a danger. I don’t want to be going home while waiting for the train and someone pushing me from behind onto the tracks because I believe in Islam. I don’t want to be walking home from the mosque one day and being murdered because I am a Muslim. I am afraid.”

Reflecting on the experience of writing about her lived reality, Tajnia shared that she was “able to let go and not be afraid of what people’s thoughts were towards me. My experience writing this piece was partially nerve-wracking because we were required to perform in front of the classroom which continues to be my fear. But it was also an experience to help with that fear and get out of my comfort zone.”

Teaching Strategies for Deep Engagement

- Establish a framework for the work. Framing units with inquiry provides opportunities for students to think about issues in new ways and provides a container for investigation. Essential questions are an integral part of this process, although they can be introduced at different stages depending on the unit and the flow of the learning.

- Provide choice. Most of the units I design begin with the whole class reading, writing, and discussing the same topics, but there is almost always a point where students are given opportunities to continue their investigation by creating a project on a topic of their choosing.

- Provide inspiration, models, and outside sources. Once students begin the process of creation, I try to flood them with sources that will help them generate ideas, research more deeply, and produce work in innovative ways. We may read and analyze a model text as a class, or I will provide students with a source bank and/or a detailed project guide.

- Create opportunities for work to be shared with a wider audience. Whenever possible I have students create work that will be seen by others and not just me. Excerpts of papers may be read aloud as we sit in a large circle, project links may be posted to an online forum where we all offer feedback, or the work may be shared with an outside audience and/or be part of a larger, outside project.

Listening to and Learning From Students

There is a continual temptation to structure learning to offer a uniform experience for all students. These efforts at standardization can feel straightforward and even logical, but experience teaches us that this is not a path most learners are interested in following.

Learning is a complex, individual process that requires teachers to balance and continually reformulate. Rifah offers teachers some important advice: “The first step should be understanding the difference between what the students actually need versus what you (the teacher) think that they need. The easiest way to spot the difference is to just talk to your students!”