Video’s Objective Eye Helps Educators Evaluate Their Habits

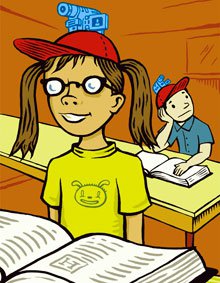

How can we see ourselves as others see us? Try putting cameras on students’ heads.

At least since Socrates, teachers have been telling students to use their heads. Now, education researchers at California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo have come up with a new and effective way to do just that, in the process reenergizing teacher assessment through a classic film technique known as point of view.

School administrators have long relied on the use of video cameras to help evaluate teachers' classroom performances. Because the quotidian demands on K-12 principals and their staffs severely limit the time they can devote both to training neophyte teachers and assessing the ongoing work of veteran instructors, video evaluations have been eagerly embraced as a time-saver.

Videography has been an unquestioned success in this realm. But it also has some serious shortcomings. For one thing, the perspective of a single fixed camera focused on a teacher provides only a static picture of the actual classroom experience. Also, the task of viewing class-length videos can be so tedious and time consuming that many subtle and telling details may be overlooked.

Teaching in 3-D

Researchers at Cal Poly have come up with a couple of wrinkles they think might transform the classroom-video paradigm. By employing head-mounted cameras on students, and using time-lapse photography, they say it's now possible to get a much more comprehensive perspective of overall classroom ambience to better measure teacher performance.

"We wanted to find out if we could see something unique or different in the performance of the teacher when we looked through the students' eyes," says James Gentilucci, who heads the school's Educational Leadership and Administration Program. "And, yes, we did. With the headcams, we got a fully dimensional perspective, and we could see clearly when the students were attending to the teacher or turning their attention to other things."

One of Gentilucci's research partners, Louis Rosenberg, an engineer as well as an educator, devised the tiny videocams that fit on baseball caps. After getting elementary school and middle school students accustomed to wearing the hats, the cameras were turned on simultaneously, along with a fixed video camera in the back of the room. Then the researchers viewed the results repeatedly with the teachers.

What emerged was revealing information about what catches and holds students' attention and what causes it to waver. For example, if in repeated instances several students are observed paying close attention to a particular instructional method (say, a demonstration) and failing to focus on another (say, a lecture), it can be inferred that those students regard lectures as less engaging.

"It's really a revelation for the teachers," Gentilucci reports. "We showed them how their voices, facial expressions, and body language generated interest and captivated attention. It's their dynamism, or lack thereof, that makes the difference."

Capturing Key Moments

Next, the research team experimented with time-lapse video. They positioned a camera in the back of the class and set it so its shutter clicked at fixed intervals, thus compressing an hour's lesson into a five-minute segment. Although the time-lapse recording doesn't render the detail-rich video capture of the headcams, it quickly identifies how teachers are using their instructional time.

"We wanted to give teachers feedback about their movement and interactions," says Gentilucci. "And there were quite a few surprises. For example, some teachers consistently interact with some students while excluding the rest of the class. If you ask them about this, they'll say, 'Oh, no, I talked to everybody. I move about in class. I'm very dynamic.' But when they see themselves in time-lapse, they can't believe how fixed and immobile they are."

Spreading the Word

When Gentilucci presented his team's findings at the 2009 American Association of School Administrators conference, in San Francisco, he found that many attendees expressed interest. This response gives him hope that this new technology will expand and enhance what is being done with video in the classroom.

"The original idea was to give teachers a better idea of their classroom performance and to develop a tool for those who evaluate them," he says. "When they can sit down side by side and say, 'Here's what a traditional video camera saw during the last 60 minutes; now, let's switch over and see what the students were looking at,' it can't help but make the job of improving instruction easier for both of them."