Community Connect: The Bluegrass State Blends Technology and Service Learning

Student-driven projects teach problem-solving, leadership, and twenty-first-century skills.

Ever since she can remember, Bailey Hamilton has listened to her grandparents reminisce about the good ol' days of Wheelwright, once a booming coal town in the eastern Kentucky mountains.

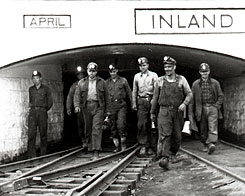

"I've listened to my Granny and Papaw talk for years about what a good place it was," says Hamilton, a junior at South Floyd High School, located in the nearby city of Hi Hat. "Back when the coal was in, it had a bowling alley, swimming pool, golf course, everything. It brings tears to my eyes to know that there's nothing left of that now."

She can't bring back those glory years, but Hamilton and her classmates are polishing and preserving those fading memories through a technology-rich service project in which they digitally restore historic photos of Wheelwright. Their efforts have culminated in a coffee table book and a companion DVD. "We're bringing back the memories, and that's so helpful to our older generation," Hamilton says.

Although Hamilton and her classmates focus their twenty-first-century skills on local history, students from across Kentucky are tackling a wide range of projects that combine technology with community service, thanks to the statewide Student Technology Leadership Program. According to Elaine Harrison, STLP coordinator for the Kentucky Department of Education, one of the major goals of this voluntary program is to "empower students with technology."

Reaching into Communities

A state advisory council started the STLP in 1994 when schools across the Bluegrass State were first acquiring computers. Initially, the program enlisted students to provide schools with technical support, and the youth learned to upgrade operating systems, install software, and help teachers troubleshoot technology problems that arose in the classroom. The program quickly expanded as students began to direct their efforts toward the larger community by building Web pages for nonprofit organizations, teaching adults how to navigate the Internet, and providing tech support for a Kentucky teachers' conference.

The statewide initiative remains viable because it allows for great flexibility. Each school or school district decides whether it wants to participate. (Finding a teacher or a community volunteer to coordinate the program in each school can be one of the biggest barriers to participation.) Each site can also choose whether to integrate the STLP into the regular school day or offer it as an after-school program. What remains consistent for all of the participating schools, however, is the emphasis on "student-driven learning through authentic projects," says Harrison. "Kids realize that what they are doing is important."

Today, Kentucky public school students from 900 schools take part in the STLP. The state also raises the stakes with an annual competition, where several thousand students compete in a range of technology areas. In one competition, kids organized into school teams vie for recognition in four categories: community service, entrepreneurship, instruction, and STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics); other contests involve Web design and computer networking. The 2008 winners included a multimedia project that taught elementary school students about positive behavior and an electronic educational resource designed to help students in many districts better understand world issues.

Kid-Powered Projects

Given the wide latitude that schools and students have within the program, those involved can neatly tailor the resulting tech projects to meet local needs and interests -- and it's often the students who do the tailoring.

At Mt. Sterling Elementary School, in Mt. Sterling, a quiet community just east of Lexington, the day begins with a closed-circuit news broadcast from the school's own television station, WMSE, which the school's fourth and fifth graders produce entirely by themselves. Adviser Jansje Huyck, a retired teacher who coordinates the school's STLP program, says that once students are comfortable operating a camera, editing footage, mixing audio, and working as a team to produce the news program, they are primed to share their expertise with the larger community. She says she then encourages her students to come up with their own project ideas.

A couple of years ago, for example, Huyck's students decided to plan an event for families of military personnel stationed at bases in the state. For the special evening event, students staffed multimedia stations so community members could make a pocket-size photo scrapbook, which they could mail to loved ones serving overseas. Meanwhile, another group of STLP students oversaw the school's computer lab, from which visitors sent email messages to the troops.

Paula Whitmer, Title I coordinator for Fayette County Public Schools, who has served as STLP coordinator in Lexington and who has also judged state competitions, says she is most impressed with student projects that use technology to address real-world concerns. "It's more than just asking, 'What can technology do for me as a kid?'" she says. "These students are asking, 'What can we do for our community?' They aren't just looking at problems. They're providing solutions."

Projects That Inspire Teachers

Back at South Floyd High School, near the former coal-mining town of Wheelwright, information technology instructor and STLP adviser Greg Moore says participating in the statewide technology initiative has revived his passion for teaching. "I couldn't ask for a better job," Moore says. "Watching students show what they can do makes this job worthwhile. When they honestly feel that they own the project, there are no discipline problems. Motivation is unbelievable. And kids help each other learn."

Moore adds that when he began his career sixteen years ago as a math teacher, he used to worry about just covering the content. "I had no flexibility or freedom," he recalls. Now, he encourages students to develop their own projects while making sure they are applying their skills to real problems.

This combination of technology, project learning, problem solving, and flexibility has certainly attracted South Floyd students to the STLP. Participation in the program is soaring: One-third of the school's 300 students sign up for Moore's information technology class, and about 50 of his students take their technology projects to another level by joining an extracurricular STLP team that competes in state and regional contests.

Bailey Hamilton, whose grandparents inspired her to commemorate Wheelwright's coal-mining history, is one of Moore's students, and she seems to be doing it all. Moore says he's observed tremendous growth in Hamilton, who learned to design Web pages and work a digital camera as a freshman, and now mentors a younger student on digital-imaging technologies. Hamilton also works with a professional photographer who once visited Moore's class.

Last year, Hamilton also took part in one of South Floyd's competitive STLP teams. She was the youngest of four girls who turned their digital-art skills into a minibusiness called South Floyd Designs. They produced sports posters and senior portraits for surrounding schools that lacked the know-how or equipment to do it themselves. The project, which raised $20,000 for the school volleyball team and other athletic programs, went on to win the STLP state championship this year -- South Floyd's first. Hamilton's team was even invited to share its project at the National Educational Computing Conference in June 2008.

For Hamilton, her many successes in community-oriented technology projects have already helped her set her sights on a future career. "After college," she says, "I want to start my own photography company."