It’s Time to Rethink the Hours America Spends Educating

Time is a resource we still haven’t figured out how to use wisely.

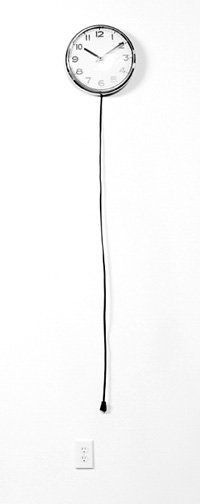

Learning in America is a prisoner of time. For the past 150 years, American public schools have held time constant and let learning vary. The rule, only rarely voiced, is simple: Learn what you can in the time we make available. It should surprise no one that some bright, hard-working students do reasonably well. Everyone else -- from the typical student to the dropout -- runs into trouble.

Time is learning's warden. Our time-bound mentality has fooled us all into believing that schools can educate all the people all the time in a school year of 180 days of 6 hours each. The consequence of our self-deception has been to ask the impossible of our students: We expect them to learn as much as their counterparts abroad in only half the time. If experience, research, and common sense teach nothing else, they confirm the truism that people learn at different rates, and in different ways with different subjects.

More Real-World Learning

<?php print l('Intelligent Design: Immersing Students in Civic Education', 'intelligent-design'); ????????>

: The architecture of building adults. <?php print l('Read', 'intelligent-design'); ????????>

Learning Around the Clock

<?php print l('Audio: An-Me Chung', 'me-chung'); ????????>

: "After-school programs can inspire the education community." <?php print l('Listen', 'me-chung'); ????????>

<?php print l('Go to Complete Coverage', 'new-day-for-learning'); ????????>

But we have put the cart before the horse: Our schools, and the people involved with them -- students, parents, teachers, administrators, and staff -- are captives of clock and calendar. The boundaries of student growth are defined by schedules for bells, buses, and vacations, instead of standards for students and learning.

Control by the Clock

The degree to which today's American school is controlled by the dynamics of clock and calendar is surprising, even to people who understand school operations:

- With few exceptions, schools open and close their doors at fixed times in the morning and early afternoon -- a school in one district might open at 7:30 A.M. and close at 2:15 P.M.; in another, the school day might run from 8 in the morning until 3 in the afternoon.

- With few exceptions, the school year lasts nine months, beginning in late summer and ending in late spring.

- According to the National Center for Education Statistics, schools typically offer a six-period day, with about five hours of classroom time a day.

- No matter how complex or simple the school subject -- literature, shop, physics, gym, or algebra -- the schedule assigns each an impartial national average of fifty-one minutes per class period, no matter how well or poorly students comprehend the material.

- The norm for required school attendance, according to the Council of Chief State School Officers, is 180 days. Eleven states permit school terms of 175 days or less; only one state requires more than 180.

- Secondary school graduation requirements are universally based on seat time, in the form of Carnegie units, a standard of measurement representing one credit for completion of a one-year course meeting daily.

- Teaching-staff salary increases are typically tied to time -- to seniority and the number of hours of graduate work completed.

- Despite the obsession with time, little attention is paid to how it is used: In forty-two states, only 41 percent of secondary school time must be spent on core academic subjects.

The results are predictable. The school clock governs how families organize their lives, how administrators oversee their schools, and how teachers work their way through the curriculum. Above all, it governs how material is presented to students and the opportunity they have to comprehend and master it. This state of affairs explains a universal phenomenon during the last quarter of the academic year: As time runs out on them, frustrated teachers face the task of cramming large portions of required material into a fraction of the time intended for it. And, as this happens, perceptive students are left to wonder about the integrity of an instructional system that behaves, year in and year out, as though the last chapters of their textbooks are not important.

A Foundation of Sand

Unyielding and relentless, the time available in a uniform 6-hour day and 180-day year is the unacknowledged design flaw in American education. By relying on time as the metric for school organization and curriculum, we have built a learning enterprise on a foundation of sand, on five premises educators know to be false.

These include

- the assumption that students arrive at school ready to learn in the same way, on the same schedule, all in rhythm with each other.

- the notion that academic time can be used for nonacademic purposes with no effect on learning.

- the pretense that because yesterday's calendar was good enough for us, it should be good enough for our children -- despite major changes in the larger society.

- the myth that schools can be transformed without giving teachers the time they need to retool themselves and reorganize their work.

- the new fiction that it is reasonable to expect world-class academic performance from our students within the time-bound system that is already failing them.

These five assumptions are a recipe for a kind of slow-motion social suicide.

The Realities of the Global Economy

In our agrarian and industrial past, when most Americans worked on farms or in factories, society could live with the consequences of time-bound education. Able students usually could do well and accomplish a lot. Most others did enough to get by and enjoyed some modest academic success. Dropouts learned little but could still look forward to productive unskilled and even semiskilled work. Society, however, can no longer live with these results.

The reality of today's world is that the global economy provides few decent jobs for the poorly educated. Today, a new standard for an educated citizenry is required, a standard suited to the twenty-first century, not the nineteenth or the twentieth. Americans must be as knowledgeable, competent, and inventive as any people in the world. All our citizens, not just a few, must be able to think for a living. Indeed, our students should do more than meet the standard; they should set it. The stakes are very high. Our people not only have to survive amid today's changes; they have to be able to create tomorrow's.

The approach of a new century offers the opportunity to create an education system geared to the demands of a new age and a different world. In the school of the future, learning -- in the form of high, measurable standards of student performance -- must become the fixed goal. Time must become an adjustable resource.

Limitations Hinder Reform

For the past decade, Americans have mounted a major effort to reform education, an effort that continues today, its energy undiminished. The reform movement has captured the serious attention of the White House, Congress, state governments, and local school boards. It has enjoyed vigorous support from teachers and administrators. It has been applauded by parents, the public, and the business community. It is one of the major issues on the nation's domestic agenda and one of the American people's most pressing concerns.

Today, this reform movement is in the midst of impressive efforts to reach the U.S. government's National Education Goals by defining higher standards for content and student achievement and framing new systems of accountability to ensure that schools educate and students learn. These activities are aimed at comprehensive education reform: improving every dimension of schooling so that students leave school equipped to earn a decent living, enjoy the richness of life, and participate responsibly in local and national affairs. As encouraging as these ambitious goals are, though, we cannot get there from here with the amount of time now available and the way we now use it. Limited time will frustrate our aspirations. Misuse of time will undermine our best efforts.

Opinion polls indicate that most Americans, and the vast majority of teachers, support higher academic standards. Some, however, fear that rigorous standards might further disadvantage our most vulnerable children. In our current time-bound system, this fear is well founded. Applied inflexibly, high standards could cause great mischief. But today's practices -- varying standards for different students and promotion by age and grade according to the calendar -- are a hoax, cruel deceptions of both students and society. Time, the missing element in the school-reform debate, is also the overlooked solution to the standards problem. Holding all students to the same high standards means that some students will need more time, just as some may require less. Standards are, then, not a barrier to success, but, rather, a mark of accomplishment. Used wisely and well, time can be the academic equalizer.

Time Constraints Are Nothing New

Time is not a new issue in the education debate; it's an age-old concern. In 1894, William T. Harris, the U.S. commissioner of education, argued in his annual report that it was a great mistake to abandon the custom of keeping urban schools open nearly the entire year. He complained of a "distinct loss this year, the average number of days of school having been reduced from 193.5 to 191," and wrote:

"The constant tendency has been toward a reduction of time. First, the Saturday morning session was discontinued, then the summer vacations were lengthened, the morning sessions were shortened, the afternoon sessions were curtailed, new holidays were introduced, provisions were made for a single session on stormy days and for closing the schools to allow teachers . . . to attend teachers' institutes . . . . The boy of today must attend school 11.1 years in order to receive as much instruction, quantitatively, as the boy of fifty years ago received in eight years. . . . It is scarcely necessary to look further than this for the explanation for the greater amount of work accomplished . . . in the German and French than in the American schools."

That document, published a hundred years ago, could have been issued last week.

The Imperative for Transformation

What lies before the American people -- nothing short of reinventing the American school -- will require unprecedented effort. The simple truth is that none of them will make much difference unless there is a transformation in attitudes about education. The reform we seek requires a widespread conviction in our society that learning matters not simply because it leads to better jobs or produces national wealth but also because it enriches the human spirit and advances social health. The human ability to learn and grow is the cornerstone of a civil and humane society. Until our nation embraces the importance of education as an investment in our common future -- the foundation of domestic tranquility and the cure for our growing anxiety about the civility of this society -- nothing will really change.

Certainly, nothing will change as long as education remains a convenient whipping boy camouflaging larger failures of national will and shortcomings in public and private leadership. As a people, we are obsessed with international economic comparisons. We fail to acknowledge that a nation's economic power often depends on the strength of its education system. Parents, grandparents, employers -- even children -- understand and believe in the power of learning. Education must become a new national obsession, as powerful as sports and entertainment, if we are to avoid a spiral of economic and social decline.

But if this transformation requires unprecedented national effort, it does not require unprecedented thinking about school operations. Common sense suffices: American students must have more time for learning. The 6-hour, 180-day school year should be relegated to museums, an exhibit from our education past. Both learners and teachers need more time -- not to do more of the same, but to use all time in new, different, and better ways. The key to liberating learning lies in unlocking time.