The Word of the Day at This School Is ‘Literacy’

At JEB Stuart High School, students can’t wait to hit the books. How’d that happen?

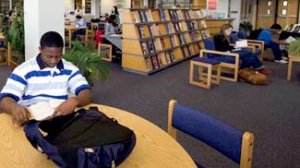

At JEB Stuart High School, in suburban Falls Church, Virginia, students keep library media specialist Amy Will scrambling to find research materials and new selections. "We had a hundred kids here this morning before 7:15," she reported one recent fall day. But it's a problem others might envy. The library -- an inviting expanse with floor-to-ceiling windows, banks of computers, and 19,000 books -- may be the most overt symbol of the school's commitment to literacy. "What we're doing is reading across the curriculum," Principal Mel Riddile says.

The focus on literacy, which permeates almost every corner of the building, from the biology lab to math classes to the chorus room, has helped transform Stuart -- once ranked among its district's lowest performers on Virginia state exams -- into an internationally recognized model of achievement. Banners tout awards from the International Center for Leadership in Education, the Education Trust, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and other organizations. Remarkably, just over half of the school's nearly 1,500 students come from low-income homes, and two-thirds speak English as a second language.

The most recent accolades came from the National Association of Secondary School Principals, which chose Riddile as 2006 Principal of the Year and named Stuart a Breakthrough High School in 2003. Executive Director Gerald N. Tirozzi praises Riddile for, he says, insisting "that all teachers teach reading. It's ultimately got to be leadership taking it on."

But team effort, a shared sense of responsibility, and an emphasis on assessment fueled Stuart's turnaround, Riddile and school personnel agree. As science chair Sherry Singer notes, "We're all extraordinarily aware of literacy here."

When Riddile arrived in 1997, he asked teachers to pinpoint the biggest obstacles to student achievement. They cited rampant absenteeism and poor reading skills: Kids missed an average of twenty-three days annually, and three-fourths of them read at least two years below grade level.

Increased vigilance and automated 6 A.M. wake-up calls pared the absentee rate to an average of seven days by 2003. Building literacy throughout the school involved a cultural shift, one that has boosted reading-proficiency scores on the Virginia Standards of Learning tests from 64 percent in 1998 to 94 percent in 2004.

Riddile started by hiring a literacy coach and amassing data. Each spring, the specialist administers the Gates-MacGintie reading test to eighth graders in its primary feeder school; those who score poorly also undergo individual screening. Though all freshmen take a required literacy course that includes online, individualized instruction, struggling readers get an additional course -- taught by a literacy expert -- for remediation on history, science, and other core subjects, and kids who need extra help receive tutoring. Stuart's A/B schedule -- classes alternate from day to day, and most class blocks are just over ninety minutes long -- provides ample time for difficult subjects.

Student progress is closely monitored throughout the school. Academic success, Riddile says, "is not about the ability of our students. It's about our ability to teach them."

As a former social studies teacher, he understood some staffers' initial resistance to thinking of themselves as reading instructors, too. "We had new state standards, they had content to cover, and nobody ever taught them how to teach reading," Riddile says. But data convinced them they needed to adapt to students' learning styles.

Professional development began with a college course and continues within the school. Louise Winney, who succeeded Sandy Switzer as literacy coach this year, observes teachers in their classrooms, modeling strategies and offering discreet follow-up suggestions. She also conducts quarterly in-service training for all teachers new to Stuart, so they learn core strategies such as the text-comprehension exercise K-W-L (know, want, learn), which asks students to jot down what they know about a subject before reading, what they want to know as they read and discuss, and finally what they've learned or still want to learn.

Second-year math teacher Y. H. Sbaiti acknowledged at a December in-service that he at first "was hesitant to try. This year, I'm really doing more of the strategies. What really cemented this is, now I'm seeing progress" in students' grasp of concepts. As math chair Stuart Singer later said, "We've found a strong correlation between literacy and math. We don't spend our time exclusively with numbers."

Monthly faculty meetings provide staff development in different kinds of literacy. The music department led a program on dynamic markings, the Italian-based signs that indicate expression on a score. Colin McDaniel, who teaches an upper-level ESL English class, conducted a content-area lesson in Nepali -- a by-product of his Peace Corps days -- in a faculty meeting so colleagues could experience the challenges confronting English-language learners.

Over the years, a common instructional language has emerged at JEB Stuart. "This gives students a structure," Winney says, adding that it creates consistency, essential for reluctant readers.

Even the coach gets coaching. Lillian Garrity, a literacy specialist in Fairfax County Public Schools' office of high school instruction, says the school district schedules training for literacy-class teachers at all grade levels as part of an intensified, systemwide literacy focus dating back at least five years.

To strengthen alignment, Riddile notes, JEB Stuart is "working with our feeder schools in the area of literacy." For example, once a month, ESL instructor Nancy Svendsen leads as many as forty-five student volunteers to nearby Bailey's Elementary School, where they read to kindergartners. A week in advance, the Raider Readers choose a picture book and polish their teaching techniques. One afternoon, junior Tony Truong practiced reading Goldilocks and the Three Bears to his friend, Rayhan Alam. Truong broke from the text to display an illustration and ask, "Which one is the little bear? Who do you think you'll see on the next page?" Han played along: "Maybe Goldilocks?"

The cognitive strategy of questioning helps "build a bridge from this book to that kid," explains Svendsen, who started the Raider Readers program about six years ago so her students could develop better reading, speaking, and leadership skills.

Spanish, Vietnamese, Somali, Chinese, Urdu, and other languages blend with English in JEB Stuart's halls. The student body is so diverse -- 41 percent Hispanic, 25 percent white, 21 percent Asian, 10 percent black, and 3 percent "other" -- that National Geographic featured it as a microcosm of vibrantly changing U.S. society in a September 2001 article.

"We're very lucky, because we have good programs and teachers who have big expectations for the students," says Nelly Samaniego, liaison to the school's Hispanic Parent Teacher Student Association. She translates for teachers when they address the association, a subset of the larger PTSA. Samaniego, whose two children graduated from JEB Stuart, was recently named Virginia's PTA Volunteer of the Year.

At least 90 percent of JEB Stuart's graduates go on to postsecondary education, Riddile says. The nonprofit JEB Stuart Scholarship Foundation, spun off from the PTSA, awards $500 to $2,000 to up to thirty-five students a year. "Some of our kids are not here legally, so they can't get aid from government," career specialist Carol Kelley explains. "Even kids who are legal have trouble affording school."

Literacy and student achievement are frequent topics in Doc's Docs, Riddile's weekly newsletter to his staff. "It's an opportunity for me to recognize faculty and to focus on specific education issues," says Riddile, who has written more than 300 issues. "Most principals don't want to write and have a bunch of teachers grading. It was threatening, but I got over it."