An Interview with the Father of Multiple Intelligences

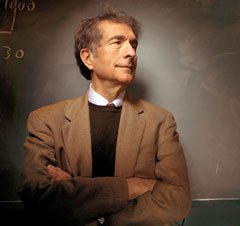

Howard Gardner reflects on his once-radical theory.

On the 26th anniversary of his book Frames of Mind, Howard Gardner discussed the impact and evolving interpretation of his groundbreaking theory of multiple intelligences. Gardner, the John H. and Elisabeth A. Hobbs Professor of Cognition and Education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, answered our questions in a wide-ranging conversation via email.

Your book presented a theory that seemed at once novel and also self-evident. Do you think teachers have found it daunting as well as liberating?

One reason for the popularity of the idea of multiple intelligences is that it can be summarized in a sentence. So the idea of a number of relatively independent cognitive capacities is not in itself daunting. What is daunting is the notion that one should therefore change one's pedagogy, curriculum, or means of assessment. But the theory says nothing about educational practice per se; it is a theory of how the human mind is organized.

Many teachers who believe in the idea of multiple intelligences complain that assessing a student's intelligence and responding with activities and curricula isn't feasible in typical classrooms. Is this a legitimate concern?

Of course, if you draw the inference that education should be individualized, an MI education for 25 or 40 kids in a class can sound daunting. It's certainly easier to individualize if you have one or just a few youngsters in your charge. But particularly in the era of new digital media, individualizing has become much easier.

There is no reason algebra needs to be taught in just one way. If software exists, or can be created, to teach algebra in numerous ways, what possible objection could there be to such individualization? And even when the software does not exist, there are many ways in which one can individualize -- for example, by having students help one another, breaking the class into "jigsaw" groups, presenting ideas in multiple ways, and so on.

I think that the problem is not changing because of MI; it is changing for any reason. Most of us would prefer to do just what we've been doing before, whether or not it has worked well.

It's been noted that many psychologists responded to Frames of Mind unenthusiastically. Was that a surprise to you? As educators have embraced the concept, has the psychology community come around?

I was somewhat surprised that the response on the part of educators was much warmer than the response on the part of psychologists. But in view of what I have just said, maybe I should not have been surprised. Why should psychologists -- and particularly psychometricians, who make their living giving IQ tests -- want to change their idea of how the mind is organized and how its capacities should be assessed?

I don't think MI theory has won many converts among hardcore psychologists, though it is typically mentioned in textbooks -- perhaps because it is hard to ignore a theory that has gained so much attention in the wider community. But the "action" is no longer in psychology -- it is in neuroscience and in genetics. In the long run, those disciplines will ascertain what is valuable and valid in MI theory, and what is of limited use or wrongly construed.

With human intelligence such a subtle and expansive phenomenon, how were you able to limit your list to the original seven? Is MI some sort of psychological string theory, with possibly infinite universes to be discovered?

After 25 years, I've added only one intelligence (the naturalist intelligence) and am considering another (the existential intelligence). And so the prospect of a geometric progression seems most unlikely. In the short run, I don't think we (as a species) are going to discover or evolve new intelligences. What happens, instead, is that already-existing intelligences get mobilized for new purposes.

Should schools try to cater to individual intelligences, or emphasize the classic idea of well-rounded students? How does a teacher respond to a student's strengths without giving up on weaker areas?

Again, this is a question of values, not a question of science or of expertise. I can envision a situation whereby parents might want to cultivate an area of strength, or whereby parents would prefer to opt for well roundedness.

My own philosophy: When children are young, we should encourage well roundedness. As they grow older, it becomes more important to discover and cultivate areas of strength. Livelihood and happiness are more likely to emerge under those circumstances.

Finally, is there a way hard-pressed teachers can use a simple, efficient approach to assessing intelligence and educating accordingly?

I don't think any teachers -- hardworking or lazy -- should adopt any educational approach unless they see the reasons for it and are helped to gain competence in that approach. This is as true for MI as it is for cooperative learning or character education or preparing for the SAT. I am not interested in efficiency per se; I'm interested in whether the approach has value and whether its results can be observed in a reasonable period of time.

I apply the three-year test. If you return to a school after three years, you want to determine the following: Does anyone even remember the initiative? Are people doing the same thing that they were three years ago? Is there a deepening process, in which the MI applications have engendered learning on the part of staff and students, and are there plans to go forward?

In light of the above question, is there a potential problem if less is expected from a student in certain areas of study because they are not his or her innate intelligence(s)?

The term "innate intelligence" harbors a bunch of presuppositions. All of us have the range of intelligences; we differ only in how easily and how swiftly particular intelligences develop. The term innate has a death sentence quality, which I reject.

That said, the challenge in education is to help students develop valued areas of knowledge, skill, and values. I don't care which intelligences are mobilized, so long as the requisite knowledge or skill or values are attained. And that is why one can learn history or math or science or values using a variety of entry points, pedagogies, and forms of assessment.

But what about the fact that teachers are so pressed for time?

A teacher who is a keen observer can learn to distinguish different intellectual strengths and styles on the fly; there is no need to resort to expensive and time-consuming assessments. I can learn a lot about the intelligences of a young child just by spending a few hours with her in a children's museum. And as for teaching in multiple ways, it is better to teach in two ways than in one, and it is better to make use of other resources -- human or digital -- rather than to try to do it all on your own.