View from the Top: A Mountain Climb Inspires Projects Across the Curriculum

Middle school students follow a climber’s journey up Mount Everest via satellite Internet while they engage in related activities in the classroom.

One day near the end of the school year, a hum of excited chatter moved through the Martin Gifted and Talented Magnet Middle School, in Raleigh, North Carolina, as students and staff shared the news that Ciprian "Chip" Popoviciu had reached the summit of Mount Everest.

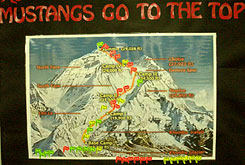

For two months, the school of nearly 1,000 students had followed the software engineer-cum-mountain climber's ascent up the treacherous mountain via a satellite Internet connection. They sympathized with him as he suffered through gastrointestinal agony, climbed steep ice slopes, and maneuvered around falling rock. Now they were buzzing with excitement bordering on anxiety as they contemplated his upcoming descent down the 29,029-foot peak.

Shrinking World

Popoviciu, an experienced climber, used a battery-and solar-powered mobile access router to communicate with the school from the mountain through a satellite modem -- except during a period when the Olympic torch ascended Everest and Chinese authorities forbade correspondence. He carried a tiny laptop, a Web camera, and an Internet-based voice-over-IP telephone to communicate with students via a secure WebEx Internet portal.

Popoviciu personally funded the Everest expedition, but his day-job employer, Cisco Systems, paid for the satellite connection and provided his communications technology. The Microelectronics Center of North Carolina (MCNC), a nonprofit organization in North Carolina that provides information-technology services to public schools and universities throughout the state, brought Martin Middle School into the project.

Students first met Popoviciu at a school assembly before he began his trip. Once he was climbing, technology enabled that connection to flourish, as he dispatched photographs and commentary regularly through the WebEx portal. "They've seen firsthand pictures from Mount Everest from someone they know," says magnet-program coordinator Lisa Thompson. "It makes the world a smaller place."

Just a week before he summitted, a group of students barraged Popoviciu with questions such as "What makes the glaciers blue?" and "How do you do laundry at such high altitudes?" during a lengthy Internet call using the free Skype program. When someone asked how he kept his spirits up during the months away from home, he talked about camaraderie with fellow expedition members. "I have to say, this project of ours is really, really helping a lot," he added.

Students also blogged about their Everest Project experiences on GoLo, a local online social-networking community, and they posted Everest-related musings and questions for Popoviciu in the discussion forums at the WebEx portal.

Getting Real

Teachers leveraged the expedition across the curriculum to make academic subjects feel more salient to students. At the same time, they forged stronger bonds with one another. Principal Wade Martin says the project brought together core and elective teachers who wouldn't ordinarily collaborate. "As a magnet school, everyone wants to showcase their program," he adds. "This took the competitive nature off the table."

The visual-arts department held a contest to design a flag for Popoviciu to take with him, and geography came to life when he carried it from New York to Hong Kong to Kathmandu and up Mount Everest, sending pictures along the way. Orchestra students played string and percussion pieces inspired by traditional Nepalese music, and a Spanish teacher organized a fundraiser for a Nepalese sister school. Even the keyboarding class got a dose of the excitement, as students learned to create tables and filled them with Everest-related data.

"We were able to do what we do as teachers," says theater arts teacher Judy Dove, who had students in her puppetry class make Asian-style rod puppets and write and perform folktales based on Popoviciu's Everest climb. But connecting the projects to his climb, she adds, "made them more focused, more personal, more meaningful."

For language arts classes, school staff and counselors worked together to design writing prompts that related eight character traits the district promotes -- courage, good judgment, integrity, kindness, perseverance, respect, responsibility and self-discipline -- to what is required to reach the "summit" of a personal goal.

Hands-On Learning

Science students considered the effects that high altitudes have on climbers by conducting their own simulations in Raleigh. For one activity, science department chair Kris Thomasson used stopwatches, calculators, straws, data tables, and a staircase to deepen student comprehension about the topic. She divided classes into two groups: test subjects and data collectors. The data collectors compiled and analyzed information on the test subjects' heart and respiration rates, both at rest and after hiking up and down three flights of stairs.

Half of the test subjects climbed the stairs with their noses pinched and mouths clenched around drinking straws. Students then compared the results for these subjects with those from other students who climbed without any breathing obstructions. This experiment illustrated the impact decreasing oxygen supply has on performance. (The air at the summit of Mount Everest has just a third of the oxygen found in air at sea level.)

The lesson hit home. One student blogger wrote, "I was in the group that had the straw, and let me tell you, breathing through a little straw is not fun. After I got to the second level of stairs, breathing was quite difficult. I give Chip props for being able to consume the very thin oxygen on Mount Everest."

Dance students, too, gained a deeper appreciation for Popoviciu's journey when dance teacher Joanna Caves had them research the environment and climate of Mount Everest to illuminate how extreme physical trials affect the body and mind. To put themselves in Popoviciu's boots, they studied Nepalese culture and customs, high-altitude medical issues, and topography. Then they choreographed a modern dance that grappled with the peril of his undertaking and the possibility of death.

"If you understand what you are afraid of, then you're a little less afraid," Caves says, describing how the dance helped the students cope with anxiety about Popoviciu's expedition. She adds, "The performance, called Everest, wound up being their greatest triumph; they conquered their own personal mountain."

Project-Based Collaboration

Students also joined in schoolwide activities, including watching the IMAX movie Everest and then wrestling with the weighty ethical and environmental questions that arose afterward. Based on this experience, they drafted critical questions for Popoviciu and his technical assistant, Cisco engineer Tim Woods, to answer during a schoolwide assembly.

All the homerooms participated in a competition to "read their way up Mount Everest," in which students metaphorically climbed the mountain by reading books and magazine articles. To reach "base camp," at least fifteen students in a homeroom had to read a magazine article or a nonfiction book on Mount Everest or related topics. Students then "climbed" 50 feet with each article and 200 feet with each book they read. Teachers observed a marked increase in nonfiction reading during the contest.

Gigi Karmous-Edwards, the principal scientist at MCNC and a Martin parent, says the combination of videoconferencing, blogging, and other collaborative network-based tools used with classroom instruction fueled the project's success.

"The key thing here is the integration of a single project across all three grades and into every single curriculum, including math, science, and language arts," Karmous-Edwards notes. "That, to me, was really spectacular and very special, because you saw the whole school mobilize around this, and it became a part of Martin Middle School."