The Advantage of Disadvantage: Teachers with Disabilities Are Not a Handicap

Disabled teachers bring a unique perspective to the classroom.

Audio:

Gary LeGates on teaching without sight

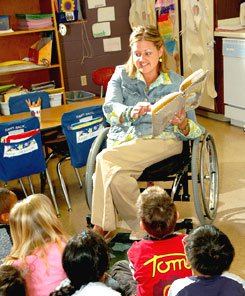

Like most new teachers, Amanda Trei had troublesleeping the night before her first day in the classroom.On top of the usual new-job jitters -- Wouldshe be a good teacher? Would the kids like her?Would she find a friend among her new colleagues? -- Trei hadan additional worry. She wondered how the special educationstudents at Schwegler Elementary School, in Lawrence,Kansas, would react to her wheelchair.

Trei was fourteen years old in 1992 when she suffered severeinjuries in a car accident. All of her ribs were shattered, her liverwas severed, a rotator cuff was torn, and her back was broken,leaving her lower body paralyzed. She spent a full year in thehospital before finishing high school and enrolling in college.Trei had planned to become a nurse. After the accident, shedecided to go into education because she felt a kinship withstudents who have learning disabilities and physical handicaps."I live being different every day," she says. "In what other jobcould I make an impact on kids who live what I live?"

On her first day -- five years ago -- Trei's students noticedher wheelchair and were curious. "A student asked me why Ineeded a car to get around -- my wheelchair car," she says witha laugh. "After they asked me about it, we went on with ourbusiness and it was cool."

Trei, who now teaches at Riverview Elementary School, inShawnee, Kansas, says she has discovered that her disability canbe an advantage in working with special education students. "Ihave a one-up on anybody who can walk, because I can seewhat my students need, and I can see the struggles they'regoing to face," she says."Somebody who isn't disabled -- they can read about it,they can watch it, but if theynever live through it, theynever really know."

Most of Trei's studentsrequire modifications to theirclassroom work. Some needextra time on tests; othersmight need to hear, rather thanread, their textbooks. "I thinkwhen they see me do things differently, they feel OK aboutthat," Trei says. "Because I'm accepted in my school, I thinkthey feel like they're accepted, too." She turns questions abouther disability into lessons on finding alternate ways to dothings. She might demonstrate to students how she gets in andout of her wheelchair, or take them to her car to show them thehand controls she uses to drive.

The idea that there's always more than one way to reach agoal is also integral to what Tricia Downing teaches, regardlessof her students' abilities. Downing, a competitive cyclist, hadbeen the internship coordinator for Denver's CEC MiddleCollege, a magnet high school, for just two weeks in 2000before she was hit by a car during a training ride. Though shewas paralyzed from the chest down, she went back to work andresumed her life as a competitive athlete, becoming the firstparaplegic woman to complete an Iron Man-distance triathlon.

"Sometimes, students get stuck in their teenage world,where everything's a crisis," she says. "I've been able to getacross to students that the world is bigger than their problems.My message is that life is full of challenges, but ifyou're willing to try to overcome them, you can find theresources within yourself."

Gary LeGates hopes his presence in the classroom hashelped dispel stereotypes about people with disabilities.LeGates, who is blind, struggled to find his first teachingjob in the late 1970s. He was hired, finally, when anotherinstructor went on maternity leave. "People were afraid tohire a blind person. I think they were afraid I wouldn't be ableto handle the classroom situation," says LeGates, who retiredlast spring after teaching Latin and French for thirty years atWestminster Senior High School, in Westminster, Maryland.

Though it wasn't always easy, LeGates found ways towork around his disability. Early in his tenure, he learnedstudents were cheating in his class. He discussed the situationwith the principal and thereafter relied on hall monitorsand community volunteers to watch students during tests.Another time, a student wrote, "I have some marijuana" onthe board in LeGates's classroom. "Half the class went to theoffice and reported him," LeGates says. "They thought thatwas unfair, because there's no way I could see it."

LeGates often surprised students with his classroom-managementskills, says John Seaman, Westminster's principal.Seaman's own son took Latin classes with LeGates in the1990s and initially wondered how a blind teacher would beable to control a roomful of teenagers. "Within two days,Gary had learned each student's name and voice," the principalsays, "and if a student responded, he knew exactly whowas speaking to him."

Seaman reports that he and his son, now in his early thirties,still occasionally talk about the example LeGates set -- of hardwork, perseverance, and scholarship. "I'm convinced that ourstudents have gained an understanding that having an obvioushandicap does not preclude someonefrom being a professional andan intellectual," he says. "We willmiss him as an influence."

Unfortunately, though, LeGatessays, schools seem no more opento blind teachers now than whenhe started his career. "People havecontacted me about the possibilityof getting teaching jobs," hesays, "and it sounds like they'refacing the same kind of thing Iwas facing." Discipline hasn't gottenany easier, he adds, and the amount of paperworkrequired of teachers has grown.

No organization tracks the number of K-12 educatorswith disabilities, and few resources are available for those whohope to enter the teaching field. Clayton E. Keller, coauthorof Enhancing Diversity: Educators with Disabilities, says districtsshould be actively recruiting disabled teachers. "One ofthe things that gets talked about a lot in nondisability diversityis, 'Are there images of people like me? Are there peoplelike me in positions of responsibility?'" Keller says. "If kidswith disabilities don't see people with disabilities in positionsof responsibility, will they think they'll ever be able to dothose things?"

Wendy Shugol, who has cerebral palsy and uses a wheelchairand a service dog, says she, too, has encountered prospectiveemployers who couldn't see past her disability. She usesthose experiences to help prepare her special education studentsat Falls Church High School, in Fairfax County,Virginia, for life after high school.

"I'm tougher on them than the nondisabled teachers,because I know what skills they need to be able to cope in thereal world," she says. "The other teachers will let them slidewhen they don't do their homework, but the boss isn't going togive you six extra days if the deadline is today."

Shugol says she pushes other teachers to let disabled studentsdecide whether to try something, rather than deciding for them."I find my nondisabled counterparts making judgments aboutstudents based on what the kids look like," she says. Years ago,she successfully lobbied for the physical disabilities departmentto offer more demanding courses such as algebra and physics,and for the school to offer late busing for her students so theycould stay for extra help or participate in clubs.

"I talked about retirement last year, and there was an uproaramong the kids, who said, 'If you retire, there will be nobodyto speak for us,'" Shugol says. "I really don't stop to think aboutmy disability very much. I've never looked at myself as a rolemodel for my students. But a number of them have said theyknew if I could do it, theycould do it."