March Madness in the Classroom?

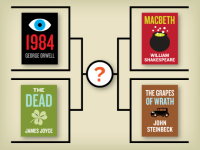

Use NCAA-style brackets to get your students passionately debating works of literature—or big topics in any subject.

The Madness of March is coming. You can feel the frenzy of Cinderella stories and brackets busting. The Big Dance. The Road to the Final Four. Call it what you want, but for three weeks, the nation turns its eyes to the NCAA tournament, falling in love with underdogs and holding its breath on each buzzer-beating shot. Hoops hysteria begins on Selection Sunday, the night when millions are glued to ESPN, waiting to see which 68 tickets will be punched to the Big Dance.

As teachers, we should create the same excitement, hope, and drama in our classes.

I do AP Lit March Madness, a journey to determine the best work of literature we’ve read all year. Brackets are made, seeding committees are formed, and each day I put a section of the bracket on the board and the works of literature back in students’ hands so that they can vote on which is the superior work. It’s all subjective—and that’s what makes it so spectacular. Students are ready and willing to defend their cherished reads. The student who loved The Grapes of Wrath may be crestfallen when it is upset by Shelley’s “Ozymandias.” Some will argue that Dickinson’s “There Is No Frigate Like a Book” should go all the way, knocking out heavyweights like Tennyson’s “Ulysses” and Orwell’s 1984. I just tally the votes and smile on the inside as students debate with impassioned voices. March Madness is a window through which you can see what your students learned, what they valued, and what they’re willing to argue for.

Toe to Toe: Wordsworth vs. Orwell

Here’s how I set it up.

Selection Sunday turns into Maker Monday in my class. I play a quick video to set the stage for the excitement that we’ll try to capture—for example, a compilation of announcer Gus Johnson’s best moments.

I tell the students that we’ll spend portions of the next three weeks in our own March Madness, determining our own literary champion.

Students are then divided into roles:

- Bracket Makers: I give them four huge pieces of poster board to tape together and make a mega-bracket. They have to compute how many brackets go on each side, the size of each bracket, and how to evenly space them. We use 32 works (novels, plays, poems, and articles).

- Seeding Committee: This group makes a master list of everything that we read, and then, just like the NCAA Selection Committee, they have to determine the four No. 1 seeds, No. 2 seeds, etc., until they have all 32 works ranked.

- Class Logo: This group brainstorms, designs, and develops a class logo and names for each region of the bracket.

On Thursday, as the NCAA tournament begins, student voting begins as well. I hand out slips of paper at the door when students enter the room. While they always remember the novels, some poems require a refresher. Those works are waiting for the students on the Smartboard, allowing them to regain a feel for voice, images, and thematic weight. I want our bracket to progress at roughly the same speed as the college tournament, so we tackle just a handful of brackets each day. Plus, the progression builds the excitement. Works gain momentum. One year, Wordsworth’s “The World Is Too Much With Us” emerged from the pack as a No. 6 seed and made it as far as the Final Four. Another year 1984 annihilated the competition. The whole experience would not have the same impact if we did the voting all in one day. The daily process only consumes about 10 minutes of a period, but its effect is lasting. Students talk about it throughout the day—the favorite marching its way to the Final Four, the injustice of an upset, the thrill of a one-point victory.

Open Season

This approach isn’t limited to literature. Social studies teachers can set up brackets for the most ruthless dictators or greatest presidents. Literacy teachers can set up brackets for favorite characters. Biology teachers can craft brackets featuring the fittest mammals. On a different tack, math students can calculate the statistics of the actual teams and make predictions for each bracket.

Be creative. The brackets are simply a context for student engagement—they make students look forward to class each day. Just be prepared for the madness that might ensue.