How to Find a Home for Service-Learning Projects

Hundreds of youth traveled to Washington, DC, this month to take part in the National Service-Learning Conference. Their stories offer convincing evidence that service-learning -- done right -- not only meets academic standards but also makes a lasting difference in the lives of young people. Communities stand to gain, too, from projects that put students in the role of change agent.

What does quality service-learning look like in practice? Where does it fit into the school day? And how can it help to transform the learning experience? Here's just one story.

Meet the Rough Writers

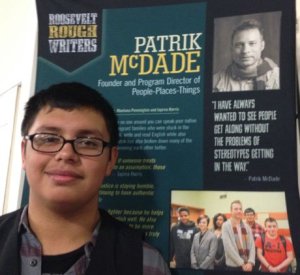

On the crowded exhibit floor at the conference, I was drawn to conversations with students from Roosevelt High in Portland, Oregon (coincidentally, my hometown). They proudly wear the title of Roosevelt Rough Writers. As ninth-grader Julio Lopez Hernandez told me, he started this school year doing a service project "as a class requirement I wasn't so excited about. By the end, it changed my life and opened my world."

Hernandez was describing the Freedom Fighters Project, which has become a tradition at his diverse urban school. An interdisciplinary Humanities project, it challenges students to uncover stories of individuals in their community who have taken a stand for social justice. Students interview these unsung heroes, write essays about them, and compile their best work into a book. In the process, they hone their writing and learn about the history of civil rights. Then they create museum-quality exhibits that they take into the community, sparking conversations about sometimes difficult topics and putting their communication skills to effective use.

The Freedom Fighters Project began as a summer experience facilitated by Kate McPherson, community engagement specialist at Roosevelt High. She went on to launch the Roosevelt High Writing and Publishing Center, a campus resource where students can consult with peers (and near-peer college students) to improve their academic writing skills. A student-led, culturally responsive solution to the achievement gap, the center aims to amplify youth voice in the community.

The Roosevelt Writing and Publishing Center is also a resource for teacher collaboration. "We want to help teachers design projects that have authenticity," McPherson explained. "The earlier we can get that started for students, the better." Two ninth-grade teachers -- history teacher George Bishop and English teacher Shawn Swanson -- have taken up the Freedom Fighters Project in the Humanities class that they teach together. They started with 90 students in 2012 and, this school year, have 120 freshmen participating in the project.

Finding a Home for Service

"I found a home for this project within the Common Core State Standards," Swanson told me. Students gain experience gathering information as they prepare to conduct interviews and put informational writing skills to use as they craft and revise essays.

The project doesn't stop there. "Students were inspired by the stories they heard, but inspiration isn't enough," Swanson explained. "I told them, you guys need to be the next Freedom Fighters." As the final phase of the project, he has students "pick an issue close to your hearts and write a speech about it." In the process, they learn to make compelling arguments and back up their words with evidence.

Hernandez wrote a powerful speech about immigration and race, which he has delivered to large community audiences. He was inspired by the Freedom Fighter he profiled. Patrik McDade promotes intercultural communication and helps immigrant families understand their rights through an organization he started, called People-Places-Things.

Hernandez not only found his confidence as a public speaker, but gained insights that will last long beyond his freshman year. Issues about immigration, race, and the achievement gap are complicated, he admits, "but it got simpler for me. I have a clearer view now. I have a better understanding of why things happen -- cause and effect. I can see others' points of view. I understand what I'm doing, where I'm going."

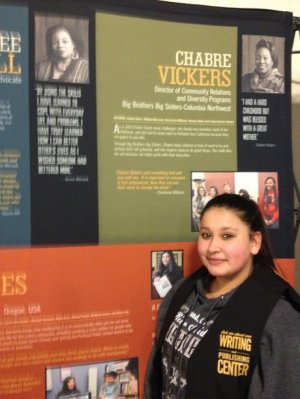

Service-learning projects naturally encourage reflection. A student named Leticia Acosta Gomez, for instance, reflected on her own young life when she interviewed Chabre Vickers, director of Big Brothers Big Sisters Columbia Northwest. Vickers and her mother were homeless during much of her childhood, but she managed to find her purpose in helping others. That resonates with Gomez, who has six younger siblings. "I try to guide them, to inspire them. I want the best for them," she says.

Another student, Breanna Mizee, learned about the discrimination faced by female athletes when she interviewed Kim Spir, now a coach at University of Portland. Mizee, who plays soccer, basketball, and softball, struggled to understand why girls were once kept on the sidelines. "I've been an athlete my whole life," she says.

Because students wanted to do justice to the stories they heard, they invested "so much time and effort," adds student Hannah Verbout. "This isn't like reading a textbook and taking notes. It's real life."

Building Community Connections

Having an authentic audience for their work has been key to the success of the Freedom Fighters Project. McPherson estimates that 3,000 people have seen the Freedom Fighter exhibits over the years, at settings ranging from the Oregon Historical Society to churches to college campuses. "That gives the project visibility," she says, and helps to sustain it.

Community members who have been recognized as Freedom Fighters have become supporters of the project, nominating others whose stories are worth telling. Building those community connections is another good strategy for sustaining quality service-learning efforts.

McPherson, a long-time advocate of service-learning, thinks strategically about how to sustain projects like this one and the others emerging from the Roosevelt Publishing and Writing Center. Students recently published a literary companion to Portland called Where the Roses Smell the Best. Bookstores, hotels, and other business partners in the community have stepped up as supporters. Meanwhile, a campaign is underway to recruit Freedom Fighter Friends whose support will help to grow the next generation of Freedom Fighters.

For more service-learning resources, project examples, and conference highlights, visit the National Youth Leadership Council website or join the recently re-launched Generator School Network. Find more conference highlights by following the Twitter hashtag, #monumental14.

Has your school found a home for service-learning? How do you keep good projects going for the long term? Please share your strategies and stories in the comments.