2 Evidence-Based Learning Strategies

Spaced and retrieval practice help students retain content and give them a sense of what they know—and what they don’t.

I often say to my students, “If a test is the first time you’re made to think about or with the class material, we’ve both probably failed.” Learning is effortful and requires cognition. As their teacher, I need to ensure that I provide my students with opportunities for demonstration of learning in the classroom.

There are many ways to do this. Your methods can be traditional and require pencil and paper or more modern with a screen and other manipulatives. No matter the technique, students should be made to work with and think with the information or content in order to increase their retention of it.

Cognitive psychology provides evidence of specific learning strategies that are wonderfully applicable and adaptable to most classrooms, no matter students’ abilities or grade level. Here are two strategies I discovered through The Learning Scientists and use in my classroom almost daily in an attempt to teach my students more efficient and effective study and practice habits and to maximize their retention of material.

Retrieval Practice

This very powerful strategy is quite easily applied to the classroom. Retrieval practice is the attempt to retrieve information from memory. This can take many forms in the classroom—low-stakes multiple-choice formative assessment, group discussion, open-ended essay prompts, etc.—and it can occur at the beginning of class, as a transition activity, or to end class.

I frame retrieval practice to my students as an efficient method of assessing their own learning. They’re either able answer the questions or not. If they cannot, this should drive further review and practice of material. I stress that it’s perfectly fine if they can’t answer the questions at this point. Isn’t it much better they attempt now (and subsequently have a better understanding of the holes in their learning) rather than attempting for the first time on the test?

Because retrieval is such an effective self-assessment tool for students, I always tell my students they should initially use only their brain to attempt to retrieve the information. If a textbook, peer, or notebook tells them the answer, they ultimately didn’t know the material.

I usually begin by not providing any cues (word banks, for example) and prefer this be more of an open-ended activity. This alleviates students’ false belief that they know information when they’ve actually just guessed correctly. Students are quite good at fooling themselves into believing they know something when, in fact, they don’t. (This is true of all people, actually.)

Spaced Practice

Spaced practice can be defined as the opposite of cramming. It is literally spacing out practice over multiple days, weeks, months, etc. I explain to my students that they’ll be more efficient and effective with their practicing if they study for 15 minutes each for three days rather than cram for an hour the night before a test. Easier said than done, I know—especially with adolescents.

I’ve created an activity to show very simply how they can incorporate this strategy into their study habits.

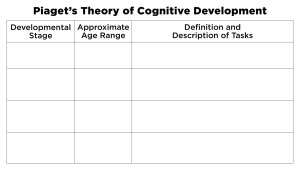

- I take some important information that usually confuses students and create a chart; in the example above it’s Piaget’s Theory of Cognitive Development.

- To begin class, I ask the students to complete the chart only using their brain. They highlight all of their answers from this step in yellow.

- Next, I have them use their notes to check their answers and complete any of the chart they didn’t complete in the previous step, and highlight these answers in orange.

- Lastly, they use their peers and/or the textbook to fill in any blanks they still have and highlight these answers in blue.

Now we grade their answers, and students have three different grades for this retrieval: one in yellow for what they knew using only their brain, one in orange for what they found using their notes, and one in blue for what they found through their peers or the textbook. The students keep their charts.

The next day or a few days later, we begin class with the same blank chart and follow the same steps. And we complete this activity one more time, usually about a week later. What students typically find is that on the second and third attempts at completing a chart, they have more yellow highlighter on their paper and less orange and blue, meaning they’ve remembered more with their brain and relied less on notes, a peer, or the textbook.

The spacing of practice has resulted in more long-term retention of material, and students now have a study practice that is much more effective than simple highlighting of notes or rereading their notes or textbook.

There are many more learning strategies (concrete examples, dual coding, interleaving, etc.), but simply adding these two learning strategies to my classroom has significantly changed my teaching and my students’ learning. There’s less anxiety about assessments since they occur so frequently. And students are much more accepting of getting questions wrong because that’s simply part of the learning process and helps them to have a truer assessment of their learning.

All of this gives my students tools to be successful in almost any class they attend in middle school, high school, or college.