Empowering Student Writers

Once students are ready to write, different strategies for revision and publication will test and stretch their ability to think critically about their own work.

In my previous post, we explored strategies to differentiate for helping student writers get a strong start on pre-writing and drafting. These phases of the writing process help students build a strong writing foundation and mediate negative self-beliefs about being writers. The second half of this process solidifies the confidence and skills that students need to successfully communicate their ideas with clarity and efficiency. Revision and publication are natural phases for differentiating writing so that all students are stretched in their writing skills.

Feedback and reflection may seem like a time crunch. Yet the results can save time in the long term because students produce higher-quality work. Ron Berger's work with Austin's Butterfly is an example of a simple protocol used by first grade students to revise their work through a series of drafts. Beware: If you watch the following video, you'll have no excuse but to establish one for all grade levels.

Revision

Here are strategies that aid creating a strong revision process.

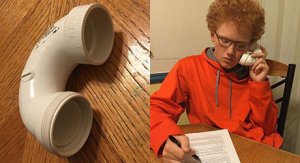

One-Foot Voice

Students hate to read their writing aloud, yet that activity helps them catch problems in mechanics, word choice, and sentence fluency.

- Writers read their draft just loud enough for them to hear their own voice.

- They mark text for the focus problems as directed by the teacher, such as action verbs or passive voice.

- After reading the draft, writers return to the marked texts to reflect on changes.

Feedback Strategies

Involving students in giving feedback helps the writer, and gives the audience members ideas on improvements to their own work. As needed, create feedback teams with a mix of skill levels or shared common interests in the topic, or create groups based on common set of skills. In all cases, students need communication structures that provide a safe environment for supporting everyone's growth.

1. Be kind, specific, and constructive.

Writers value feedback that helps them grow. Saying "That's a great opening" does not tell a writer that the reader connected to the opening anecdote -- unless he or she says so. "That opening needs work" provides no constructive input. An alternative: "I wonder how your summary could end with an anecdote that ties together the main points?"

2. Use starter stems when giving feedback.

Students are more likely to consider feedback from peers than hearing those same words spoken by the teacher. Reinforce a safe culture by having student comments begin with starter stems. This process helps authors find solutions for themselves as opposed to being told what to do.

- "I like. . ." identifies what works in the author's product. It's important to recognize successes so that the author can hear the suggestions for improvement.

- "I wonder. . ." invites the author to consider a concern that needs addressing. The language does not demand. Instead, it encourages reflection of potential gaps or needs.

- "What if. . ." invites consideration of explicit suggestions. The author may follow or discard the ideas as he or she sees fit.

Jan Chappuis' How Am I Doing? is great guide for feedback. Education Northwest's 6+1 Trait Writing gives focus to teachers and gives students areas to offer suggestions. The language of the traits makes peer feedback and teacher coaching specific and constructive.

3. Use commenting tools.

Two tools that support student reflection are the Comments and Track Changes features. Comments is a tool found in most word-processors, including Google Docs, usually under the Insert menu. Peers and teachers highlight text and insert feedback comments directly on the electronic draft, framed by the starter statements mentioned above. This gives the author a written record of the feedback to review. The teacher can also review the feedback for coaching the peers on being kind, specific, and constructive.

Track Changes is similar to Comments, but is found only in Microsoft Word. In addition to posting comments in the margin, Track Changes records any edits to the document. A related tool for reflection is Revision History found in Google Drive. These help teachers analyze the author's thinking process when revising.

Publication

When students are required to publish, they're more receptive to working through the writing process. Publishing helps students focus on an audience, and draft and revise based on the needs of their viewership. Publication is often misunderstood as being final. Posting work online can lead back to revisions based on comments by viewers. Experts from anywhere can add comments on work as a way to mentor the student's thinking. In a public forum, other students also view the comments to incorporate into their own work.

Blogs and wikis are places for immediate publication and a forum for feedback. Once work is posted, students can still revise to further polish, allowing them to progress at their own learning pace. Feedback is ongoing if the published work is considered part of each student's portfolio.

Some venues for blogging are: Blogger, WordPress, Weebly, and Tumblr. Some commonly-used wikis are: Google Site, PBWorks, and Wikispaces.

Processing Power

Process is a key element of differentiated instruction. Students learn best when they have opportunities to make sense of the skills to understand what they know and do not know. The writing process meets this need, and is addressed in ELA writing standards such as Common Core (Wri#5), TEKs (Wri#13), and SOLs (Wri#6). The coaching of writing should be a concrete set of actions so that all teachers succeed in assisting their students to deepen their skills and create amazing writing.